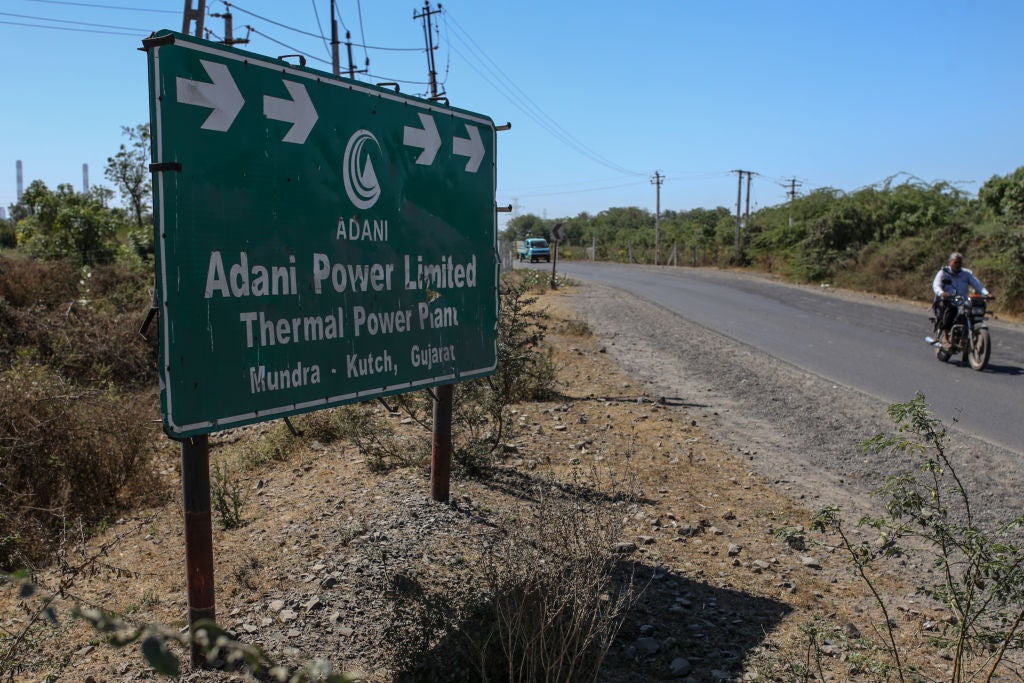

It has been a tricky few months for Adani, the colossal Indian conglomerate known for being the world’s largest private developer of new coal mines and coal-fired power plants. In January, short-selling research company Hindenburg alleged that the Adani Group had engaged in fraud, corruption, stock manipulation and money laundering, as part of what it called the “largest con in corporate history”. Adani denies Hindenburg’s allegations. The market response was swift, with the stock price of each of the Adani Group’s subsidiaries – including its renewable energy company Adani Green Energy – plummeting.

Historically, Adani Green Energy has successfully convinced investors that its renewable energy business is a wholly separate entity to the one responsible for its coal operations – so much so that the Group has raised billions of dollars worth of debt tied to green proceeds (including a $750m, three-year green bond launched in 2021 by Adani Green Energy, or a $300m, ten-year sustainability-linked bond issued by Adani Electricity Mumbai that same year).

All the while, the Group is the world’s third-largest backer of coal power expansion, according to data from German non-profit Urgewald.

Activists such as the Stop Adani campaign have long argued that Adani’s subsidiaries should be thought of as a single entity, and as such, any investment in green debt issued by the company is inadvertently financing coal expansion.

Recent revelations – in the wake of the Hindenburg report – that Adani had leveraged capital from a large network of shell companies involved in opaque financial transactions across the group – have confirmed this view.

“One of the most significant things that have happened recently” was the revelation that “Adani was using Adani Green Energy stock as collateral for a loan against the Carmichael Coal Mine [a controversial coal mine owned by the Adani Group], showing the capital was not at all quarantined from the more controversial projects”, Nick Haines, senior campaigner at climate group Ekō (formerly SumOfUs), tells Energy Monitor.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataLast week, three Adani subsidiaries – Adani Green Energy, Adani Transmission and Adani Ports and Special Economic Zone – were removed from the UN-backed Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi) following a formal request from Ekō and climate group Market Forces to review the company’s inclusion in the scheme in light of the recent allegations.

The SBTi removed a handful of other companies – including Naturgy Energy Group, Snam and Centrica – because its recently updated policy on fossil fuels now excludes companies with any level of direct involvement in exploration, extraction, mining or production of them, irrespective of percentage revenue generated by these activities.

This could be a serious blow to Adani Green Energy’s reputation, given that the SBTi is considered the most reputable source for validating corporate net-zero strategies; some investors even include loopholes within their fossil fuel restriction policies for companies that are SBTi signatories.

According to a press release from Ekō, the Adani’s Group’s “comeback rests strongly on the gamble that Adani Green Energy is the most salvageable Adani brand to international investors – an assumption now called into question by its delisting from the SBTi”.

This could be particularly damaging given that Adani Green Energy is preparing to raise up to $800m in new debt in the coming months.

In a February report on Adani’s coal legacy, Tim Buckley, director of Australian think tank Climate Energy Finance, argued that as Adani is “investing far more in new fossil fuel projects than in zero emissions alternatives”, it is “undermining its ESG claims to be the green energy champion of India”.

Buckley added: “A silver lining of Hindenburg’s report… is that India may see the folly of pursuing an expensive imported fossil fuel expansion plan that increases India’s energy security risks. We would suggest India would be far better off doubling or trebling its domestic sourcing of zero emissions, deflationary, cheap renewable energy infrastructure, leveraging the enormous interest from global investment capital [in that].”