The Paris Agreement does not mention fossil fuels and the COP27 conclusions did not mention oil and gas, so a growing number of nations, cities, institutions and Nobel laureates say it is time for a Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation Treaty. The small Pacific nation of Vanuatu was the first government to endorse this concept and is channelling all of its diplomatic efforts to build international support for this cause, as the publication of the final instalment of the IPCC’s Sixth Assessment Report reminded governments that urgency, not solutions, is lacking.

Vanuatu’s diplomacy recently scored two victories: first, it succeeded in convening a briefing in mid-March with the non-profit Center for International Environmental Law (CIEL) in Geneva to discuss an International Court of Justice (ICJ) opinion on states’ legal obligations on climate action. A request for that opinion was formally sent to all UN member states by Vanuatu and 15 supporters on 20 February 2023. Second, Vanuatu convinced a block of six Pacific countries to commit to a “Fossil Fuel Free Pacific” as a prelude to global action on fossil fuels after a Pacific ministerial dialogue in Port-Vila, Vanuatu, on 17 March.

What is a Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation Treaty?

The Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation Treaty (‘Fossil Fuel Treaty’) is a proposal for a new treaty to manage a just transition away from coal, oil and gas. It would complement the Paris Agreement and draw lessons from other treaties that have sought to manage global threats like landmines, tobacco, chemical weapons, ozone-depleting chemicals and nuclear weapons.

The proposal has three key pillars: “non-proliferation”, or preventing the proliferation of coal, oil and gas by ending all new exploration and production; a “fair phase-out”, or equitably winding down existing stockpiles and production, where wealthy nations transition fastest; and a “just transition” that leaves no worker, community or country behind.

“COP28 will be in a petrostate [which] means putting fossil fuels at the heart of our discussions,” said Harjeet Singh, head of global political strategy at the NGO Climate Action Network (CAN) International and engagement lead for a new Fossil Fuel Treaty, in an interview with Energy Monitor in March 2023. “The war in Ukraine is being funded by a fossil fuel bonanza,” he added.

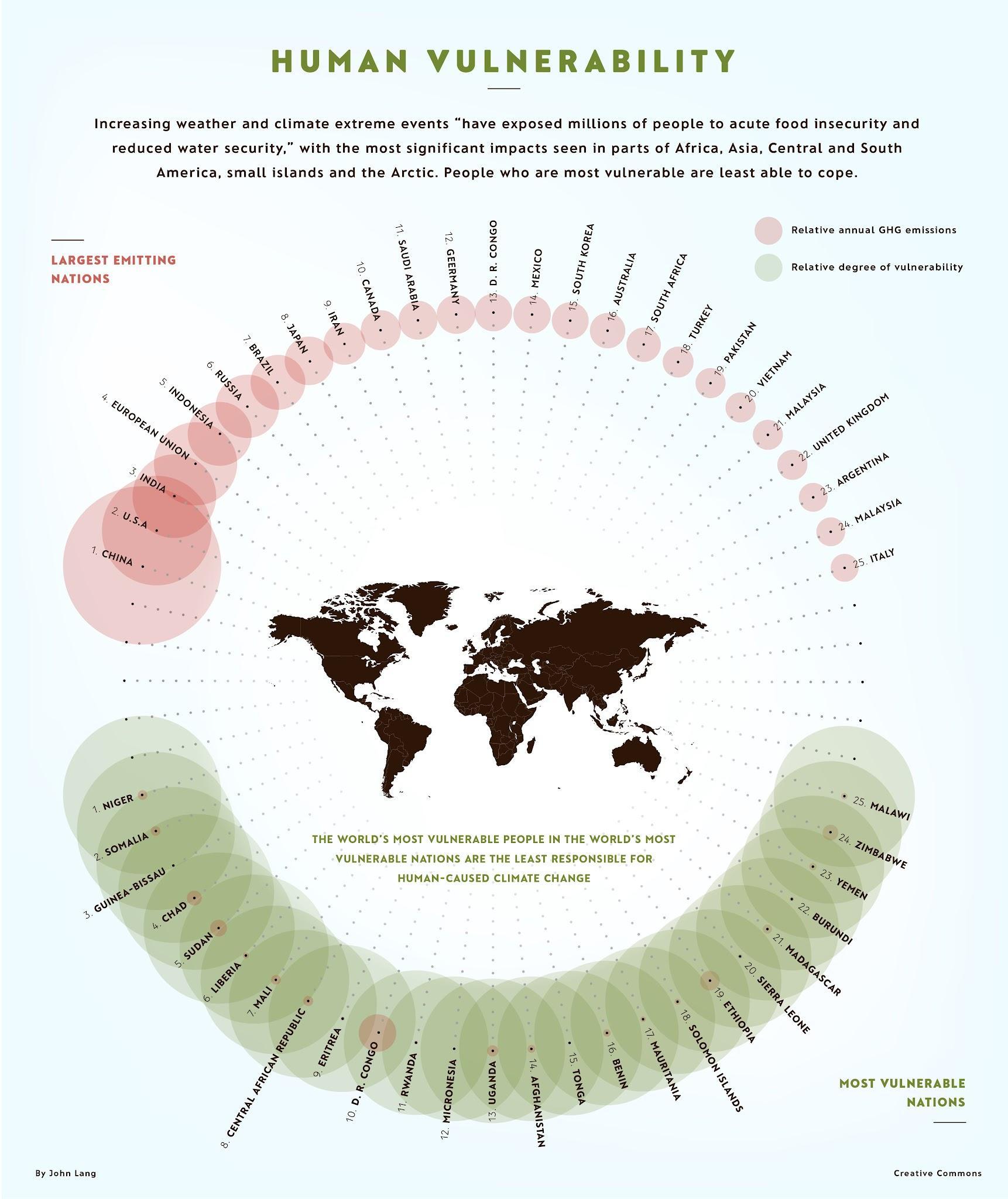

Rich countries that have the resource and capability to move away from fossil fuels are still drilling for oil and gas. Countries in the Global South are having to prioritise adaptation over mitigation.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataDespite his misgivings, Singh sees momentum behind the Beyond Oil and Gas Alliance, launched at COP26, and a new Fossil Fuel Treaty. “While the UNFCCC and the Paris Agreement are focused on reducing emissions, the Fossil Fuel Treaty is about stopping expansion and an equitable phase-out of fossil fuels,” he says.

“Since [we have] a global registry of fossil fuels, we know how many fossil fuel producers in the Global South continue with the extraction to repay debt,” he adds.

However, businesses so far remain sceptical of the initiative. The Canadian Energy Centre, an Alberta provincial organisation primarily supported by an industry-fed government fund, considers that “calling for a total shutdown of oil and gas development around the world would only hurt humanity”. “The Fossil Fuel Treaty is the wrong path to take… [because] the world’s growing population requires abundant, reliable, affordable energy in order to thrive,” it says.

Will the ICJ rule on climate action?

At COP27, a group of countries led by Vanuatu demanded that “humanity” be put at the forefront of decision-making. This led to the 20 February 2023 request to all UN member states to ask the ICJ to issue an opinion on states’ obligations on climate action. Vanuatu led the request with 15 others (Angola, Antigua and Barbuda, Bangladesh, Costa Rica, Federated States of Micronesia, Morocco, Mozambique, New Zealand, Portugal, Romania, Samoa, Sierra Leone, Singapore, Uganda and Vietnam).

The resolution, which has drawn 127 sponsors, will be voted upon at the 77th session of the UN General Assembly (UNGA) on 29 March 2023. If approved – by simple majority – it would effectively give the ICJ a mandate to hold states accountable for their (lack of) climate action under international environmental law and human rights law for the first time in history. The ICJ opinion would not be legally binding but it would be highly influential. The court would be empowered to provide guidance for states, to address the root causes of climate change and its impact on human rights and on intergenerational equity.

“The advisory opinion could be an opportunity for the Court to crystallise recent developments on the interpretation of states’ obligations in the context of climate change,” says Sol Meckievi, a research associate at the Cambridge Centre for Environment, Energy and Natural Resource Governance. “Important developments have resulted from the systematic interpretation of human rights and environmental law, which in turn, have translated into an obligation to implement more ambitious climate policy.”

“Whereas many of these developments have had a limited scope of applicability [for example, specific countries], an ICJ advisory opinion would be of importance for the whole international community,” she adds.

Why should business care? Meckievi says: “[First,] although the advisory opinion focuses on states’ obligations, the decision could potentially be useful for the interpretation of the responsibilities of other entities that contribute to climate change. Second, the advisory opinion is expected to have important implications for the implementation of states’ obligations. From this perspective, the implications for business corporations are unavoidable considering that as major contributors to climate change and entities subject to the state’s regulatory power, any decision on greenhouse gas emissions could have a direct effect on their activities.”

“Every increment of warming from now to 1.5°C will be significant for small island states (SIS),” emphasises Sindra Sharma-Khushal, global policy lead at CAN International. SIS are among the most vulnerable nations because they lack access to finance, she adds, which would enable them to adapt and address loss and damage.

“Public and private finance flows for fossil fuels are still greater than those for climate adaptation and mitigation,” says the Fijian national. “The science is clear. It is a matter of political will now. The survival of many SIS is a matter of political will.”

Nikki Reisch, director of the climate & energy programme at CIEL, stated on a Twitter space prior to the UNGA vote that “the key objective of the initiative is to inform policy making”, with a view to ratcheting up ambition to what scientists say is necessary. “Tomorrow’s vote is a test for countries to show in which side of history they stand,” she said.

The call for a ‘Fossil Fuel Free Pacific’

From 15–17 March 2023, ministers and officials from the Kingdom of Tonga, Niue, the Republic of Fiji, the Republic of Vanuatu, the Solomon Islands and Tuvalu met for the 2nd Pacific Ministerial Dialogue on Pathways for the Global Just Transition Away from Fossil Fuels held in Vanuatu.

The meeting took place during a state of emergency after Vanuatu was hit by an unprecedented two category 4 cyclones and an earthquake within 48 hours, as per their website. It resulted in a call for a ‘Fossil Fuel Free Pacific’. “It is not acceptable that countries and companies are still planning on producing more than double the amount of fossil fuels by 2030 than the world can burn to limit warming to 1.5°C,” reads the resolution that was adopted.

“Faced with devastating climate impacts resulting from the world’s continued addiction to fossil fuels, Pacific governments have once again demonstrated what true leadership looks like,” said Romain Ioualalen, global policy lead at the NGO Oil Change International, in a press statement.

“International climate negotiations are failing us,” added Suluafi Brianna Fruean, a Samoan climate justice activist. “This dialogue of Pacific ministers is stepping outside of the box and acknowledging that we must try new ways to save ourselves.”

“At COP28… a full phase-out of fossil fuels, that has to be the outcome,” says Christopher Bartlett, who manages the Vanuatu Government Climate Diplomacy Program. “The United Arab Emirates is a petrostate but also a leader in renewables, and it is currently in talks with Vanuatu.”

For Bartlett and Vanuatu, a fossil fuel phase-down is not enough, hence the call for a new legal framework that directly addresses fossil fuels as the root cause of greenhouse gas emissions. The Fossil Fuel Treaty would complement the UNFCCC and should be legally binding, Bartlett says.

“The Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) doesn’t require nuclear states as signatories,” he argues. “As long as a majority of other countries are on board to set a new international norm […this can begin] to contain proliferation.” Although the NPT did not ultimately prevent nuclear proliferation, in the context of the Cold War arms race and mounting international concern about the consequences of nuclear war, the treaty was a major success for advocates of arms control because it set a precedent for international cooperation between nuclear and non-nuclear states to prevent proliferation.

Pakistan never signed the NPT, but it would benefit from the Fossil Fuel Treaty – the country suffered unprecedented flooding that inundated a third of the country in 2022. This tragic event underpinned the country’s negotiating power on a Loss and Damage Fund at COP27 under the motto “What goes on in Pakistan will not stay in Pakistan”.

“We are all in the same boat and dependent on fossil fuels,” Bartlett sums up. “The more we can do in solidarity, the easier it will be to bring petrostates on board. At the COP we must get away from the ‘you did this, we need that’ narrative between North and South. Existential threats are for all, the Pacific Islands are just the tip of the iceberg.”

The six Pacific nations that initiated the call for a Fossil Fuel Free Pacific hope to escalate this to a global call in 12 months. Bartlett believes that if the ICJ draft resolution is adopted at the UNGA 64th Plenary meeting on 29 March, it will send a powerful signal that states’ obligations on climate action may extend the confines of the UNFCCC.