Since Gustavo Petro became Colombia’s president in August 2022 he has insisted that the country’s energy transition rests on two pillars: replacing the foreign currency from coal and oil exports with income from other exports – mainly clean energy and ecotourism – and instilling a carbon-free capitalism: during the World Economic Forum (WEF) in Davos in January, he asked: “Can capitalism overcome the climate crisis that it helped to cause?”

Tuesday 7 February 2023 marked the first six months of the Petro administration. Among several progressive social policies, one that stands out is the recent announcement of an end to the granting of new oil and gas exploration licences. This raised more than one eyebrow and many questions: how much oil and gas does Colombia have left? How would it replace those revenues? How will it persuade the private sector to invest in clean energy?

A wake-up call to the climate crisis

During the WEF in Davos, Irene Vélez-Torres, Colombia’s Minister of Mines and Energy, said: “We decided that we are not going to award new gas and oil exploration contracts […] as part of our commitment to the fight against climate change because we know that this decision, which is planetary, is absolutely urgent. We reviewed existing contracts and it was determined that they would guarantee the national gas supply until beyond the year 2037 and there may even be surplus resources.”

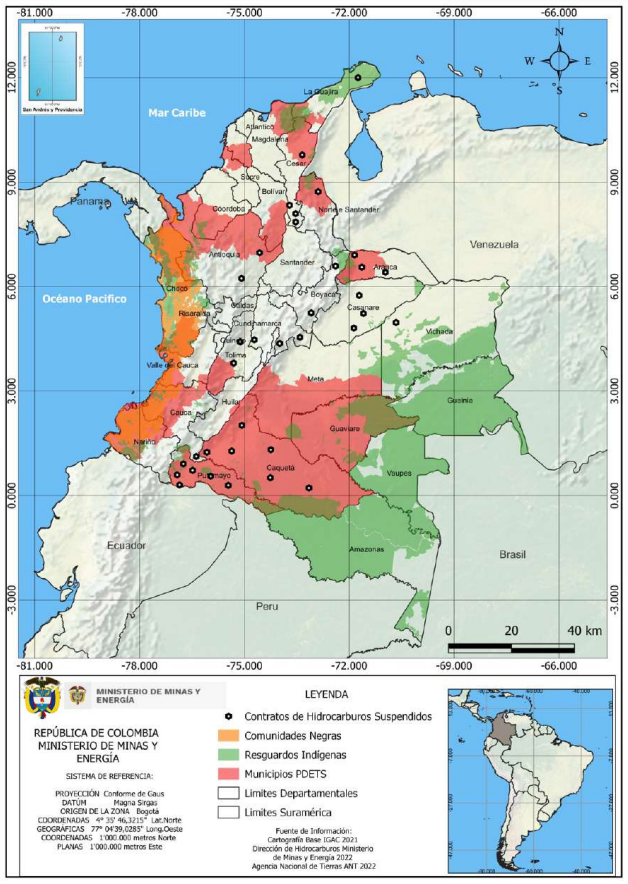

The government’s plan is to “strengthen existing contracts and unlock the suspended ones”, while beginning a “progressive and gradual” energy transition to more renewables and the democratisation of power generation.

This plan is based on a report released last December entitled Balance of hydrocarbon contracts and resources available for the Just Energy Transition, which caused controversy due to the following statement: “It is possible to infer that the contingent resources, both from the Sinú 9 block and from the offshore discoveries, can supply the national demand and, even, produce a surplus in its production until the year 2037. If we take into account the prospective resources this supply can be extended to the year 2042.” In other words, Colombia does not need new oil and gas fields.

For Alejandro Fula, a researcher at the National University of Colombia, the government’s calculation is optimistic. “We have [oil and gas] reserves for eight to ten years [respectively], but that period is not [long] enough to make the transition or the transformation of Colombia’s economic base,” Fula told Energy Monitor.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalData“A plan is also needed to reform rail and river transport to reduce dependence on oil: we consume 305,000 barrels of liquid fuels daily and import up to 20% of all our gasoline. It is urgent to gradually reduce that dependency. Colombia is about to become one of the first large-scale electric car assemblers in the region, and we should take advantage of that.” According to the Observatory of Economic Complexity, Colombian exports in 2020 were $32.2bn (157.49trn pesos), with crude petroleum representing 23.2%, coal briquettes 12.8%, gold 7.28%, refined petroleum 4.82% and palm oil 1.28%.

Fula suggests that the Ministry of Mines and Energy’s controversial new report lacks rigour. “In my opinion, she [the minister] does not present false figures but mixes expectations with observations,” Fula says. Proven, probable and possible reserves need to be better distinguished, he adds. “In any case, conceiving the energy transition as something rapid is thinking with desire, since the infrastructures and necessary industrial conversion take from ten to 20 years,” the researcher concludes.

Andrés Gómez, an oil engineer and researcher for CENSAT-Agua Viva, an environmental NGO, says there needs to be a clearer distinction between exploration and exploitation. “The new oil discoveries are marginal, and even if there is gas, it is in ultra-deep waters – at a depth of 2,500m – which raises costs and the risk of stranded assets,” Gómez told Energy Monitor. “There is a natural decline of reserves in the country, which is why players like the national oil company, Ecopetrol, are already preparing for new economic alternatives such as a change in the law that allows them to become generators of electricity.”

The bumpy road map for a just energy transition

Until the end of 2022, representatives from the private sector, such as the Colombian Natural Gas Association, Shell Colombia and Ecopetrol said they were interested in working side by side with the government to accelerate the energy transition. However, on 8 February – in the aftermath of the energy minister’s announcement in Davos – the Colombian Association of Oil & Gas presented a report warning that private investment in oil and gas exploration in the country will fall by 33% in 2023.

“The relationship with the private sector is tense since public electricity and gas prices have risen a lot, so the executive has had to intervene [to curb them],” says Fula. “It is better to try to reconcile positions, because the investments and major changes needed for the [energy] transition can only be made jointly by the state, large foreign investors and the Colombian energy sector.”

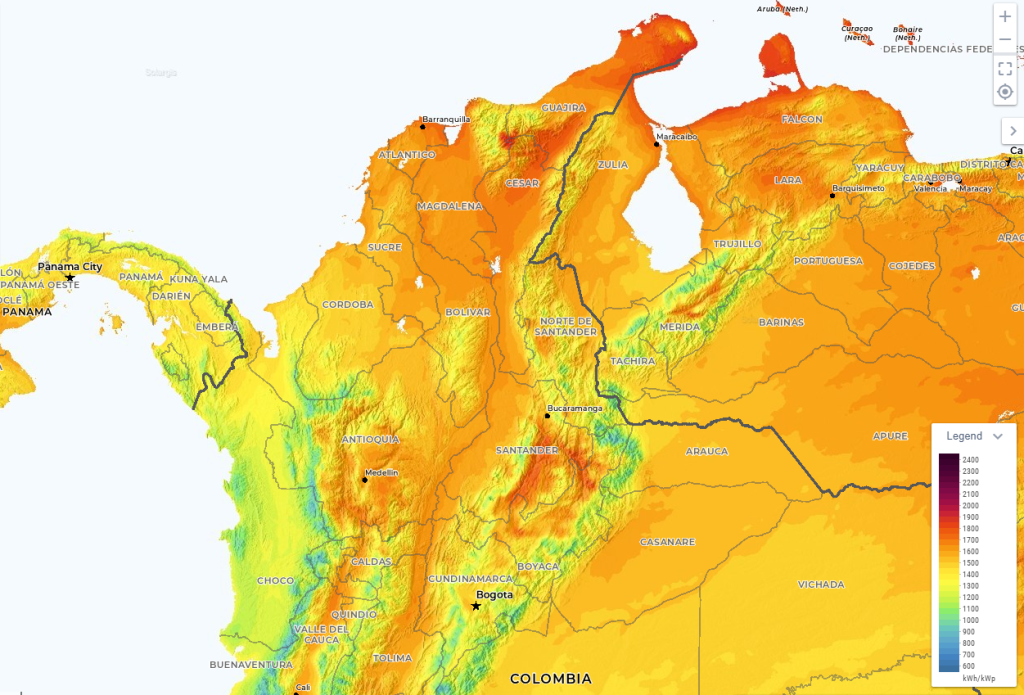

The government’s Roadmap for a Just Energy Transition is based on dialogues with local and indigenous communities, which is crucial for a region such as La Guajira, which accounts for 36% of national coal production but has also felt its impacts, such as air and water pollution. Despite a solar and wind boom in the region, there is also a sense of renewed extractivism that bypasses local communities including the largest indigenous nation in the country, the Wayuú. That is why Minister Vélez-Torres is insisting that new wind and solar projects must be carried out with maximum environmental safety and recognise a territory’s cultural characteristics and the principle of social responsibility.

To combat the energy poverty in many off-grid areas, the energy ministry wants to implement the model of energy communities with solar-powered microgrids and community (co-)ownership of generation. However, Miguel Hernández Borrero, president of the Colombian Solar Energy Association, which has more than 106 corporate members, says that to date, the government has yet to reach out to them. “We are looking for a way to bring our entity closer to the government, so that they have our experience and technical capacity [to help build out Colombia’s solar sector],” he says.

For Gómez, the government’s declaration in December 2022 of no more open-pit coal exploration contracts means that around 300,000 tonnes of coal will remain underground. “This is effective climate action, since it exceeds the [pledges in Colombia’s national climate plan submitted to the UN] by almost three times. … But if hydraulic fracturing [‘fracking’] and unconventional [oil and gas] deposits were left in the ground, that would be a much bigger action in terms of emissions.”

Colombia only has 0.1% of global oil reserves, he adds. “The oil union wants to continue exploring, but we have already passed peak oil and non-conventional peak oil in the world.”

Colombia: The energy transition challenges ahead

Gustavo Petro and Francia Márquez – former environmental activist, winner of the Goldman Environmental Prize and now vice president of Colombia – have stuck to their campaign promises since they took office. Their agenda has been about tackling extractivism and the inequality suffered by black and indigenous populations across the country as well as priorities included in the government’s National Development Plan for 2022–26.

At COP27, Petro’s message was a first for Latin America and the Caribbean: he presented a “decalogue” of actions in the face of the climate crisis and recognised the role of indigenous people as keepers of the Amazon rainforest. Márquez also attended the UN summit and called for an alliance between Latin America, the Caribbean and Africa to end “environmental racism”.

More recently, Petro and his Chilean counterpart Gabriel Boric came together to ask the Inter-American Court of Human Rights for an advisory opinion on states’ human rights obligations related to the climate emergency.

Colombia’s announcement at Davos that it intends to end new oil and gas exploration was celebrated by the Danish government, which invited Colombia to join the Beyond Oil & Gas Alliance created at COP26. Fula believes the foreign ministry should seek out strategic alliances to promote the decarbonisation of the Colombian economy and create well-paid jobs in engineering, science and innovation. “Since we are members of the OECD, we must propose national and international alliances for technological development.”

🇩🇰 minister @DanJoergensen: “Encouraged by announcement from Colombian minister @IreneVelezT at #wef that government of @petrogustavo will not grant new oil and gas exploration licenses. DK ready to support ⚡️ transition through @beyondoilgas alliance & bilateral 🇩🇰 cooperation”

— Denmark MFA 🇩🇰 (@DanishMFA) January 22, 2023

He also endorses a government plan to sell CO2 capture through forest conservation. “This can be a bridge to the world of decarbonisation and an opportunity to regenerate territories where forest was cleared for livestock, such as in Caquetá and Guaviare.”

According to Fula: “We must spend the [income from] fossil resources to get rid of fossil dependence. How much fossil fuel does the energy transition in Colombia require? Nobody knows. What we know is that the time horizon of the reserves can be doubled if we consistently reduce exports and [invest in] the industrial transformation of our country.”

For Gómez, Petro is an example of global leadership. “It is the first time that a moratorium on new oil exploration and exploitation contracts is proposed in a country with a long oil history such as Colombia […] understanding that 56% of its exports [today] are oil and coal,” he says.

[Keep up with Energy Monitor: Subscribe to our weekly newsletter]

The International Renewable Energy Agency estimates that eight million jobs will be lost in the oil industry globally, but that the low-carbon energy transition will create 11.8 million new ones. “At Ecopetrol, there are union sectors for and against the transition,” says Fula. “Senior managers have said that fracking is not essential for the company’s future viability but that it would promote the creation of jobs.”

Social unrest persists in places like Puerto Wilches in the Magdalena Medio region, where fracking was rejected after the union of palm oil producers opposed it, but opponents are still receiving death threats from its proponents.

There is also scepticism of energy transition initiatives. “Colombia suffered the expulsion of rural communities through paramilitary forces to develop palm oil fields for biodiesel,” Fula explains. “After 50 years of war, with leaders assassinated, these communities are closed to any new proposals presented as ‘development’.”

Environmental lawyer Rosa Peña works at Aida, an organisation that provides legal counselling to Latin American communities suffering environmental harm. From Bogotá she explains how Colombia historically lacked territorial planning and failed to diagnose the risks of megaprojects such as the Hidroituango dam: in May 2018, a failure in the construction of the hydroelectric dam caused flooding, landslides, avalanches and the evacuation of more than 25,000 people.

Today, there is no regulation for the proper management and closure of big energy and mining projects, Peña warns. The closed Prodeco and Cerrejón coal mines are leaving behind perpetual environmental liabilities. Since mining giant Glencore sued Colombia before the World Bank’s International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes, civil society is asking Petro to withdraw from international treaties that could undermine the government’s capacity to see through its social and environmental priorities.

The government will also need to convince the private sector, independent experts, NGOs and other governments that it can deliver an energy transition. So far, Colombia has yet to take up Denmark’s invitation to join the Beyond Oil & Gas Alliance, but Petro and Márquez’s supporters took the streets on 14 February to defend the government and advocate for a just energy transition.

Correction: Typos in Alejandro Fula’s and Miguel Hernández Borrero’s names were corrected post-publication on 16 February.