The sight of a forlorn and dishevelled Sam Bankman-Fried, former CEO of one of the world’s largest cryptocurrency exchanges, being led away in handcuffs in the Bahamas last month aptly embodied the current plight of an entire industry. After numerous scandals and trillions of dollars wiped off its value in 2022, crypto finds itself on its knees with the vultures circling. Systemic change now seems unavoidable, and the industry can either take the bull by the horns or be forced to by the red-tape mafia waiting in the wings.

A good place to start would be the industry’s outsized environmental footprint, which currently exceeds that of many countries. Yet some within the industry are rising to the challenge. In September 2022, Ethereum, the world’s second-largest cryptocurrency platform (‘ether’ is second only to Bitcoin), almost nullified its power demand through an event called the Merge. By replacing the blockchain’s “proof-of-work” (PoW) mining mechanism with an alternative coined “proof-of-stake” (PoS), Ethereum cut its electricity consumption by 99.84% – a reduction equivalent to the annual power requirements of Ireland or Austria.

Although energy consumption is just one part of crypto’s environmental problems, and it would be premature to declare the Merge an outright victory, the move does offer cryptocurrencies everywhere a possible path towards environmental sustainability. Whether they choose to follow it is another matter.

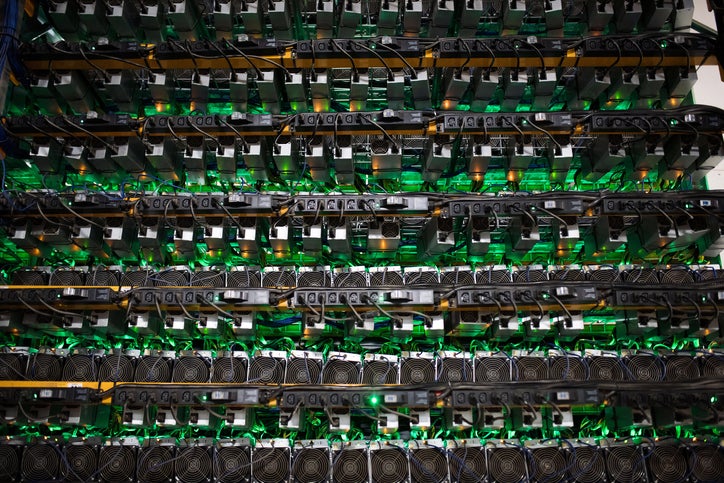

Crypto’s filthy footprint

Although estimates of the total environmental footprint of all crypto assets vary, it is thought that the electricity demand of Bitcoin alone exceeded 13GW, with an associated carbon footprint of more than 65 million tonnes of CO2 (MtCO2), in 2021. That demand is just over half that of all global data centres combined and represents nearly 0.5% of global electricity consumption. The associated carbon footprint is bigger than the global CO2 reduction created by all electric vehicles. On top of that, other cryptocurrencies were estimated – prior to the Merge – to add another 50% to Bitcoin’s energy demand.

One recent study indicated that Bitcoin has a greater climate impact than gold mining. The research from the University of New Mexico judged the climate cost of various commodities in relation to their overall market capitalisation. The results found that the climate damage from producing Bitcoin has averaged 35% of its market value over the past five years, peaking at 82% in 2020. That is comparable to 33% for beef production or 46% for natural gas extraction.

“Since Ethereum’s Merge, I would hazard an educated guess that Bitcoin now represents 90% of crypto’s environmental footprint,” says Alex de Vries, a digital currencies researcher at the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataElectricity consumption is not the only problem, though. Crypto also has an issue with electronic waste. The hardware used to mine the various cryptocurrencies regularly becomes obsolete. In fact, the annual electronic waste of Bitcoin is equivalent to that of the Netherlands. “And that is just Bitcoin,” says Carmine Russo, formerly a visiting researcher at the Centre for Climate Finance & Investment at Imperial College Business School, UK, and now a PhD researcher at the University of Naples Federico II, Italy. “But consider that there are more than 20,000 cryptocurrencies out there!”

Shifting to green crypto

As crypto’s climate impact has become ever more apparent, regulators have begun sharpening their knives. In some places, the bloodletting has already started. In spring 2021, the Chinese government cited environmental concerns as it introduced a countrywide ban on crypto mining – effectively evicting most of Bitcoin’s global mining network.

In March 2022, the European Parliament toyed with a similar ban but settled instead on additional environmental disclosures for crypto asset service providers from 2024. However, the European Central Bank wrote in a July report that it was “highly unlikely” that European authorities would not pursue crypto mining further – and potentially ban it outright.

In the US, the state of New York is poised to introduce new legislation banning cryptocurrency miners from receiving behind-the-meter power from fossil fuel plants. However, mine operators that have already filed paperwork for new or renewal permits are exempt, including the controversial Greenidge Generating Station on the western shore of Seneca Lake. Additionally, a report from the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy released in September 2022 recommended promoting “environmentally responsible crypto-asset technologies”. Legislation to “limit or eliminate” energy-intensive cryptocurrency mining should be introduced if other measures prove ineffective, it added.

Change is also coming from within. In 2021, a coalition of around 200 cryptocurrencies teamed up with think tank RMI to create the Crypto Climate Accord. The signatories agreed to reduce the carbon emissions from their electricity consumption to net zero by 2030, partly using carbon offsets but also by switching all blockchain technology to renewable energy sources by 2025 and using energy tracking tools such as so-called green hashtags.

Arguably the largest shot in the arm for the green crypto agenda, however, has come from Ethereum’s Merge – a small change in the software that effectively replaces the energy-intensive mining process altogether. Blockchains, the technology underlying cryptocurrency, are literal chains of blocks of data; updates to the network are processed within those blocks, which are then added to the end of the chain. No single party is in charge of that process; instead, anyone can proffer their computer hardware to assist in the block-creation process, with a reward offered for every created block. The difference between Bitcoin’s PoW and Ethereum’s PoS relates to how new blocks are added to the blockchain.

With PoW, the block-creation process is purposely made computationally challenging. New blocks are added to the blockchain only when a “miner” obtains a valid PoW, which can be achieved only through an iterative process of trial and error that is “best described as a numeric guessing game”, says de Vries. A correct guess completes a block, allowing the winner to add it to the blockchain and claim the reward. The more guesses the miner can generate, the greater their chance of winning. The process repeats indefinitely after every newly created block. “Before the Merge, the Ethereum network generated around 900 billion of these guesses every second of the day, non-stop,” says de Vries.

With PoS, however, the network does not incentivise participants, or “minters”, to compete on computational power to create new blocks. Instead, the block selection process is primarily based on wealth. Minters must buy some of the native currency from a cryptocurrency platform, which is then used as collateral in the “staking” process – a minimum of 32 units of Ether, in Ethereum’s case. The software then randomly chooses a “staker” to create the next block for the blockchain. The larger the amount staked, the greater the chance of being chosen. While minters still need a device with sufficient storage capacity and an active internet connection, the computational power of the device is irrelevant. This negates the need for vast mining networks of electricity-gorging computers. “A laptop will suffice,” says Russo.

Ethereum’s transition to PoS has reduced its power demand by between 99.84% and 99.9996%, according to a range of estimates, setting a benchmark for decarbonising the world’s remaining PoW-reliant cryptocurrencies. “This is the solution to getting rid of the majority of crypto’s energy consumption,” says de Vries. “It solves almost the entirety of the industry's environmental impact.”

Indirectly, it goes a long way to solving crypto’s e-waste problem, explains Russo. “Because the participants aren’t competing on computational power, they just need a laptop to confirm a transaction, rather than huge amounts of computer hardware that regularly needs replacing when it becomes obsolete.”

No panacea

However, despite the evident promise of the Merge, the purported 99% reduction of Ethereum’s power demand does not quite tell the whole story. The ‘ASICS’ devices that used to mine PoW Ethereum can still be used to mine the cryptocurrencies Ethereum Classic and EthereumPoW – a spinoff that maintains the PoW mechanism. Indeed, days after the Merge, the pair had absorbed a quarter of Ethereum’s hashrate (the marker of its mining activity) – and it was still around a fifth a month later.

Furthermore, the GPUs (a type of computer hardware) formerly used to mine Ethereum can be repurposed to mine other cryptocurrencies, thereby negating some of the Merge’s saved power consumption. However, that would likely come at a cost to miners. For instance, miners on Ethereum Classic can only earn around $0.5m a day compared with the $22.1m they could make from mining Ethereum – in turn reducing the power expenses they can afford. “I’m mining at a loss,” TheCrowbill, an Ethereum Classic miner, told The Defiant on 27 September. “Probably will remain that way for some time.”

[Keep up with Energy Monitor: Subscribe to our weekly newsletter]

Similarly, many of the GPUs may have been repurposed to focus on other energy-intensive activities such as cloud computing, AI and gaming. There is also a suspicion that Bitcoin miners have pounced on the data centre space that has become available as result of the Merge. Between 250,000 and 500,000 Bitcoin mining devices are thought to remain unused for a lack of data centre rack space.

Finally, although the Merge makes Ethereum one of most energy-efficient cryptocurrencies, it still remains less efficient than more centralised alternatives. The underlying blockchain technology replicates data and processes over thousands of participating devices, resulting in more data redundancy and higher associated energy costs from maintaining multiple copies. For example, for the roughly 1.1 million transactions a day that Ethereum processes since the Merge, the average electricity consumed per transaction ranges from 0.8 to 14.7 watt-hours (Wh). A Mastercard transaction, by contrast, consumes just 0.7Wh on average.

Converting Bitcoin’s sceptics

Nonetheless, many of these issues would be redundant if all cryptocurrencies switched from PoW to PoS. So, unlike many industries, crypto’s path to decarbonisation appears relatively simple. The very sizeable snag, however, is that the Bitcoin community – the source of the lion’s share of remaining emissions – has shown little willingness to make the move.

The Change the Code campaign launched by Greenpeace in 2022 aimed to convince Bitcoin to ditch PoW, but it was met with outright hostility by much of the community. They see the software’s immutability as one of its foundational strengths and the source of its enduring value, and due to the network’s decentralised structure, it is hard to imagine convincing the entire community to make the jump.

“The solution is there, but now you need to get this really stubborn community to think about adopting it,” says de Vries. “That is the hard part, especially since there is nobody in charge who can enforce the decision.”

It is made even more difficult by the fact that many in that community are notoriously unconcerned by climate change. “A lot of the loudest influencers in the Bitcoin community are climate change deniers, who often make statements like, ‘we breathe out carbon, so how can it be so bad?’” adds de Vries.

Ethereum has, however, proven that it is possible to convince a disparate, doubting community to shift to PoS, without any resulting increase in much-dreaded centralisation. The apparent success of the Merge may convert a fair few of Bitcoin’s doubters. “You don’t necessarily need to convince the entire Bitcoin community,” notes de Vries. “You just need a critical mass."

A transition to PoS by Bitcoin would likely result in more climate benefits than the Merge, as unlike the GPUs formerly used to mine Ethereum, Bitcoin’s ASIC-based devices cannot easily be repurposed.

Net-zero crypto

The possibility of crypto ever reaching net-zero emissions is inextricably wedded to Bitcoin’s adoption of PoS or a similarly energy-efficient mining mechanism – and if and when that will happen depends on who you ask. Much will depend on the direction of the price of Bitcoin going forward. “If the price goes up again consistently, I don’t see the community considering a change in the software,” says de Vries. “But if it keeps going down, they will have a serious [financial] concern on their hands and will be much more willing to contemplate changes.”

If governments were to slam a range of adverse regulations on Bitcoin for continuing to use PoW, de Vries also believes much of the community would soon change its tune. “In the end, money talks,” he says.

Considering the Merge reduced Ethereum’s power consumption by 99%, Russo believes that if all the other cryptocurrencies followed suit, the industry could reach net zero “in a few years”. He points out that it took Ethereum five years to complete the transition. “So let's say that on average, we need ten years to do this with other cryptocurrencies,” he says. “I think in 15 years, if crypto still exists, it will be a much more sustainable environment.”

Ultimately, for Bitcoin, the writing is on the wall – or, more accurately, in the source code. Around 19 million of the planned 21 million Bitcoins have already been created. And when that quota is filled, there will be no incentive for mining left. That will be great news for the environment; the only downside is that is not forecast to happen until 2140. “For humanity’s sake, let’s hope it doesn’t come down to that,” says de Vries.