In all the justifiable panic over climate change, it is easy to forget the world also faces a biodiversity crisis. Wildlife populations have plummeted by an average of 69% between 1970 and 2018, according to the latest WWF and Zoological Society of London biennial Living Planet Report – and the problem is only getting worse: two years ago, that figure stood at 68%, and four years ago, it was at 60%.

In a bid to protect the planet’s “vital carbon and biodiversity reserves” such as old-growth forests, peat bogs or mangroves, at COP27 in Egypt last year, France’s President Emmanuel Macron announced the creation of a “high-level group… tasked with making recommendations on the creation of a biodiversity credit market”.

This summer, that market took a couple of steps closer to reality. At the Summit for a New Financial Pact in Paris in June, France and the UK launched the UK-French Global Biodiversity Credits Roadmap, setting out a plan for scaling up global efforts to support companies buying credits that contribute to the recovery of nature. That followed the announcement of a pilot project by Swedbank that will generate biodiversity credits – the first such move by a bank.

Indeed, the likes of the UN and World Economic Forum (WEF) are backing biodiversity credits to boost conservation financing, but critics warn the new financial instrument may give companies another tool for shameless greenwashing. So, how would these “biocredits” work, and how far away are they from becoming an established market?

“A purely positive investment in biodiversity”

Spinning off the model of the carbon credit, biocredits serve as a potential revenue stream to finance biodiversity conservation and management. As a unit of biodiversity conservation effort, supported by an underlying scientific methodology, biocredits are traceable and tradeable, thereby creating incentives for biodiversity preservation.

See Also:

With global biodiversity frameworks and plans perennially dogged by a lack of funding, often overshadowed by more pressing crises such as climate change, biocredits offer a way of channelling private capital into effective nature conservation and restoration, as well as supporting locally led action by indigenous peoples and local communities.

How well do you really know your competitors?

Access the most comprehensive Company Profiles on the market, powered by GlobalData. Save hours of research. Gain competitive edge.

Thank you!

Your download email will arrive shortly

Not ready to buy yet? Download a free sample

We are confident about the unique quality of our Company Profiles. However, we want you to make the most beneficial decision for your business, so we offer a free sample that you can download by submitting the below form

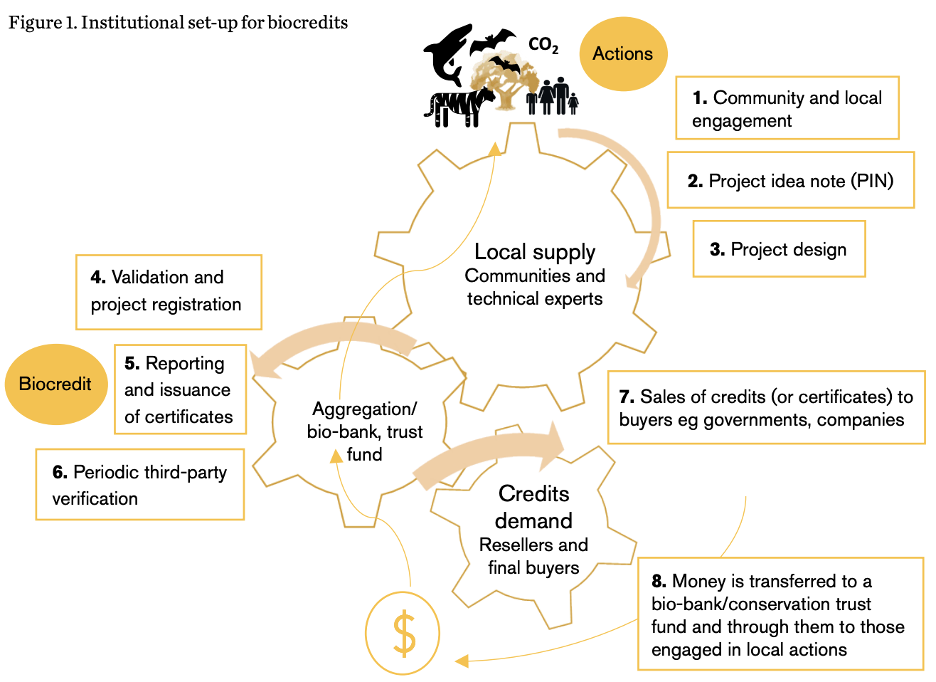

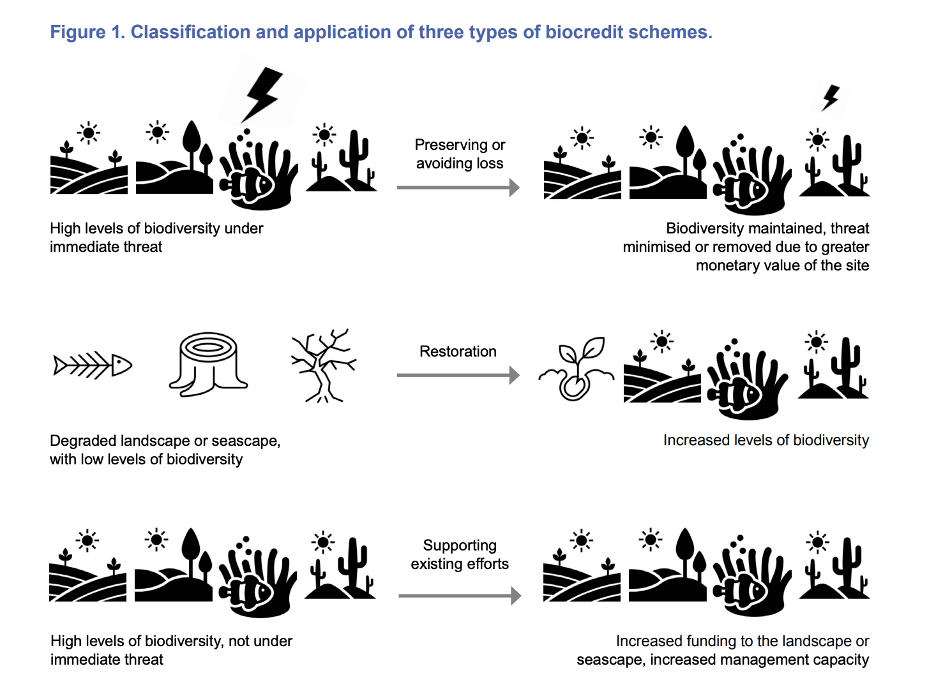

By GlobalDataBiocredit schemes, sometimes coined ‘voluntary biocredits’, typically take one of three forms by channelling conservation funding into: areas that have been previously degraded and require restoration; areas at risk of degradation and that require protection; and areas not at immediate risk, but where previous efforts have been made in their management that need to be rewarded and continued. These credits can be sold by public or private landowners, or by conservation NGOs; and bought – often via market intermediaries – by environmentally conscious companies, philanthropists or impact investors, or even individuals interested in conservation. Governments and supranational organisations have an important role in enabling policy to regulate and facilitate the market transparently and efficiently.

“One important distinction is that voluntary biodiversity credits are different from biodiversity offsets in that they don’t represent compensation for biodiversity damage done elsewhere – they are a purely positive investment in biodiversity,” says Anna Ducros, a nature economist at the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED), a sustainable development think tank based in London.

In the Swedbank scheme, for example, the bank has invested an undisclosed sum in a project that will generate biocredits from around 13 hectares of the Orsa Savings Forest in Sweden over 20 years. The credits come from a mix of initiatives in three different areas. In these areas, the credits have been assigned a value based on cost and lost income for the landowner and creation of biodiversity-promoting measures. Every five years an independent third party will carry out a follow-up conservation inventory to evaluate the development of the area’s animal and plant life.

“It is a first step to explore how financial institutions can contribute to a positive development related to biodiversity, and how a potential financial instrument can be constructed to such an end,” says Ulf Möller, head of forestry and agriculture at Swedbank.

Biodiversity credits: potential pitfalls

However, developing a stand-alone market for biodiversity credits is far from a simple task, as demonstrated recently by the numerous scandals emanating from the rainforest carbon credit market. The challenges derive from three main issues: how a biocredit scheme can effectively measure a unit of biodiversity; how a scheme can set up the market architecture for generating sales of biocredits; and how the revenue from a biocredit scheme can be channelled to key stakeholders, particularly indigenous peoples and local communities.

First, for the market to function, there must be clear and accepted metrics underlying the biocredits. These metrics must be flexible enough to evolve with an improved understanding of what quality biodiversity means and with revisions to frameworks such as the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species and the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework. Quantifying biodiversity is already tricky, but defining a unit of biodiversity in a way that is marketable, tradable and provides additionality is even more challenging. To assess net changes in biodiversity, biocredits need to be linked to a particular geographic location, be valid over a defined period and be measurable against an established baseline.

Keep up with Energy Monitor: Subscribe to our weekly newsletter“We are not dealing with something like carbon where one metric tonne of CO₂ is the same everywhere,” says Ducros. “Biodiversity is highly variable in different areas and means different things to different people.”

Attempting to solve this conundrum, Colombian company Terrasos, for instance, defines its biocredit as a transactional unit that represents positive contributions to biodiversity in an area of at least 10m², within a preserved and or restored ecosystem, that is managed for at least 20 years. Terrasos quantifies the biocredit based on four factors via its Voluntary Biocredit Quantification calculation. Each factor is given a score and normalised using the average for that factor and then they are added up to create the credit number. The factors are as follows:

1. IUCN risk category of the ecosystem: Higher risk equals higher score, ranging from 1–1.5.

2. Preservation vs. restoration: Restoration scores higher (1.5) than preservation (1).

3. Permanence: Credits must have a minimum operation time of 20 years. An operation time of 20 years gives a continuity score of 0.1 and increases to 1.0 at an operation time of 30 years.

4. Ecological connectivity: If the biodiversity improvements generate no increase in connectivity, the credit scores 0. The score for this factor increases as connectivity increases (connecting previously unconnected areas = 1.3, connecting two previously unconnected protected areas = 1.5).

Second, to ensure cost-effective biocredits, schemes need to set a price that is low enough to attract buyers and high enough to financially support meaningful biodiversity improvements and engagement with indigenous peoples and local communities. However, one of the key impediments to ecosystem markets is the high cost of meeting both biodiversity and financial criteria, including the required monitoring and verification. Transaction costs for biocredits – such as monitoring and evaluation, the cost of writing and enforcing contracts, and the cost of discovering market prices – can vary widely and have long been a restriction to developing biocredit schemes because they reduce the profit a biocredit scheme can generate.

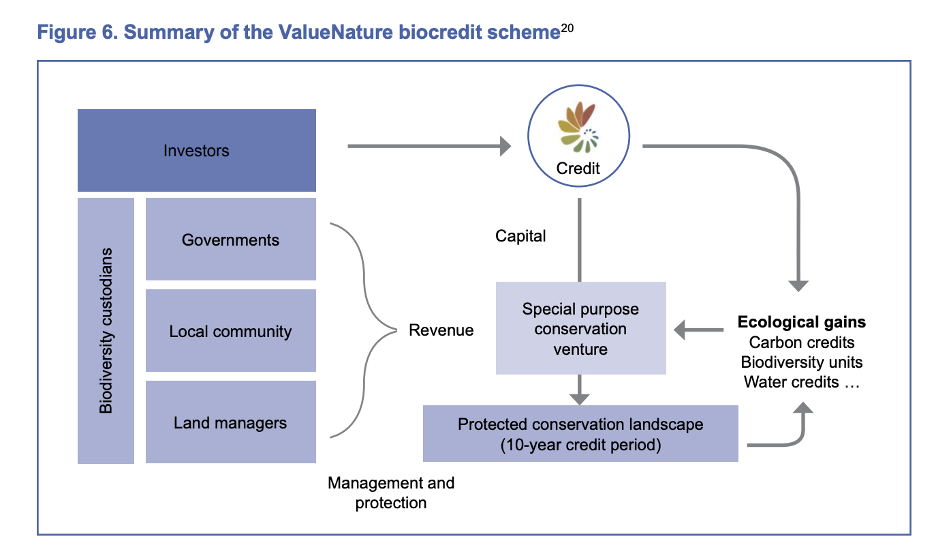

To find that price sweet spot, South African start-up ValueNature determines the initial offering price by evaluating the minimum amount required to adequately ensure the persistence of biodiversity in a concession for that decade with decent management. Of the sale price, 80% goes to biodiversity custodians (land managers/owners, indigenous peoples and local communities, and government), while the remaining 20% is reserved for biodiversity assessments, reporting, certification and trading of the digital certificates. During the ten-year time span of credit development, the buyer can re-list and sell the digital certificate if they choose to, and royalties are allocated to the biodiversity custodians. At the end of the ten-year period, final assessments are completed and the digital certificate for each hectare is ‘minted’ as the final biocredit, which is held by the final owner as an asset. Credit owners have first rights to purchase the next ten-year credit period, which ultimately has a rolling 30-year permanence window. Biocredits capitalise a Special Purpose Venture, which secures conservation of landscapes and seascapes and protects them.

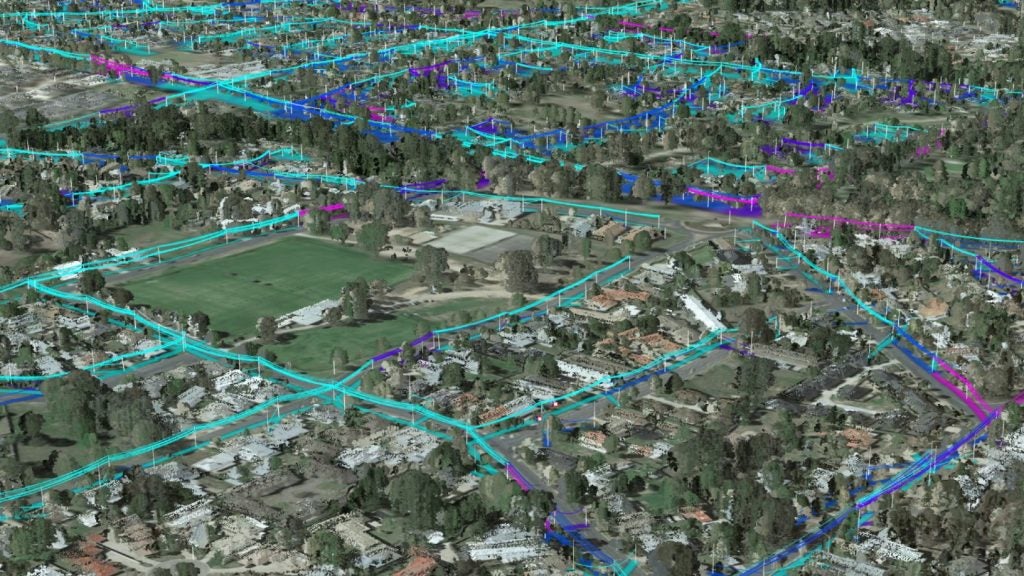

However, fast-developing technologies are rapidly making biocredit schemes more cost-effective. This includes monitoring and evaluation technology such as remote sensing, bioacoustics, metabarcoding and AI, which can account for the species richness of the site, as well as the abundance of each of those species weighted by a measure of ‘importance’ in the eco-region. Many schemes are now using distributed ledger technology (DLT) or blockchain approaches for registry accounting systems and for distributing revenue back to pre-agreed stakeholders. DLT systems can lower the transaction costs and provide enhanced measurement, reporting and verification, as well as high levels of transparency and trust.

“The pace of development of biodiversity monitoring technology over the last five to ten years has been one of the main tipping points that has made biocredits financially feasible,” says Ducros.

Finally, previous biodiversity schemes have often failed to ensure that biodiversity finance flows to support locally led action that prioritises the needs of indigenous peoples and local communities. High transaction costs and historic power imbalances, compounded by lack of transparency in how the finance is flowing, along with weak and inequitable governance systems, have too often prevented indigenous peoples and local communities from benefitting from market-based conservation schemes.

Indeed, increasing financial flows to rural areas can in some cases deepen power imbalances, lead to biodiversity mismanagement or result in conflict. In some areas, governance structures may not be immediately equipped to deal with an increase in revenue flows, and conservation efforts sometimes restrict access to livelihoods in areas like forestry, fisheries and farming. Market-based conservation schemes have previously faced criticism for ignoring the values, needs and desires of indigenous peoples and local communities in pursuit of their more reductionist approach to commodifying nature.

“In contrast to what we have seen in the carbon credit market so far, we are trying to make sure that at least 60%, even as much as 80%, of the biocredit revenues go to indigenous peoples and local communities,” says Paul Steele, chief economist at the IIED.

Read more from this author: Oliver GordonThe Wallacea Trust, a UK-based biodiversity and climate research organisation, pays a large percentage of its revenue to indigenous peoples and local communities. In all the rePLANET and Biodiversity Credit Company projects where carbon and biocredits are sold stacked together, at least 60% of the issuance price of the credit is required to be paid to local stakeholders (owners, users and managers of the site). However, all sales contracts also have a 60% indexation clause so that any profits made from reselling the credits or from rises in world prices by the time the credits are retired – and once the biodiversity improvement has been achieved – are paid back as bonus payments to the local stakeholders.

Nonetheless, despite these attempts at negating the potential pitfalls for the biocredit market, some remain unconvinced. Jonathan Crook, a policy analyst at the non-profit Carbon Market Watch, points to the difficulty that carbon credits have had quantifying the amount of carbon saved in projects, which would pale in comparison to the challenge of doing the same for biodiversity. “A tonne of CO₂ is quite easy to measure and compare, but a standardised metric for biodiversity is much more complex,” he says. “That should give serious cause for concern.”

Crook believes publicly funded programmes or funds run by governments, multilaterals or foundations would be better equipped to support biodiversity than a market-based mechanism. Approaches such as agroforestry are also better at managing lands that reduce human impact and foster biodiversity. “A lot of the negative impacts on biodiversity have to do with the widespread use of pesticides, herbicides, deforestation for cattle for meat production, etc., and there are more direct ways of addressing them than a crediting system,” he says.

However, Steele counters that with the ongoing crises surrounding the war in Ukraine, the cost of living and inflation, public money is scarce at present. The new Global Biodiversity Framework Fund, for example, was ratified by 187 countries in August and has so far attracted a mere $160m in commitments – a drop in the ocean of what is required. The 2021 State of Finance for Nature report by the UN Environment Programme estimated that around $133bn per year currently flows into nature-based solutions, and private finance accounts for only 14% of that sum. That figure needs to hit $536bn annually if the world is to address biodiversity loss. “So, we need to mobilise more private capital, as well as capital from ordinary citizens, to complement the limited public capital out there,” says Steele.

“Publicly funded conservation areas by governments can work, but we have also seen that fail,” adds Simon Morgan, ValueNature’s founder. “Biocredits would also complement carbon credits. Climate goals and biodiversity goals should be considered alongside one another and intersections between them established.”

“A market is fast emerging”

According to Steele, there are currently around 30 biocredit schemes across Africa, Asia, Latin America and Europe. “Every week, we are hearing about new developers – so a market is fast emerging,” he says. Surveys from the IIED, WEF, industry body the World Business Council for Sustainable Development and consultancy McKinsey & Co. have all demonstrated corporate appetite for biocredits. In Davos in January 2024, the WEF will host a pilot auction for biocredit schemes to kick-start the global marketplace.

Aiming to add to WEF’s ongoing work in the space, the Biodiversity Credit Alliance (BCA) was introduced last December at the UN Biodiversity Conference (COP15) in Montreal to develop a broad setting of principles and standards under which a high-integrity biocredit market would function. The coalition includes conservation practitioners, academics and other specialists, as well as a strong task force of biodiversity credit project creators and standard setters like Plan Vivo, Terrasos and rePLANET. It is also backed by the UN development and environment programmes, and the Swedish International Development Agency.

“The market is so nascent and emerging so fast that it would be a risk to have a monopoly approach at this stage,” says Steele. He believes the UK-France initiative would add welcome government momentum to the cause, if it complements rather than competes with the ongoing work of the WEF and BCA.

“A lot of the narrative around biodiversity credits is that they are five to ten years behind carbon credits, but things are moving really fast, and many biocredit projects are already operational,” adds Ducros.