In the heart of South America, Brazilians and Paraguayans point to a stretch of the Paraná river known as ‘Itaipú’, which in the Tupi indigenous language means ‘the singing boulder’. This is where the 14GW Itaipu Binational hydroelectric plant is located. By February 2023, the Itaipu dam had produced more than 2.9 billion megawatt hours (MWh) of hydropower since it began operating in 1984. Its daily generation alone prevents 87 million tonnes (t) of CO2 emissions – equal to Paraguay’s total forecast emissions for 2024 – compared with coal-fired power generation.

With 20 generating units providing an installed capacity of 14,000MW, in 2022, the plant supplied 86.40% of all the electrical energy that Paraguay consumed and 8.72% of Brazil’s total demand.

Discover B2B Marketing That Performs

Combine business intelligence and editorial excellence to reach engaged professionals across 36 leading media platforms.

Itaipu dam under new management

The Itaipu dam treaty was signed in 1973 between the dictatorships in power at the time in Brazil and Paraguay. It does not allow Paraguay to sell its hydropower – Paraguay owns half the resource – to other countries than Brazil, or other companies.

Half a century later, Paraguay is the fifth-largest energy exporter in the world – with an export value of around $1.74bn (Gs12.58trn) – but has never taken full advantage of its tremendous hydropower resource for domestic development. It is one of the poorest countries in South America. More and more Paraguayans now believe they have been locked into a bad deal with Brazil, also since sales to the country have been at below market prices. In 2019, a scandal broke with the disclosure of secret negotiations in which the Paraguayan government accepted unfavourable terms demanded by Brazil for the sale of its hydropower. Paraguay annulled the diplomatic minutes in an attempt to prevent the president’s impeachment.

In the upcoming presidential elections on 30 April, the ruling Colorado Party – which ran the country from 1946 to 2008 and again from 2013 – risks losing its grip on power. The opposition alliance Concertación – under the lead of the Liberal Party – has a real chance of returning to government, as it did in 2008.

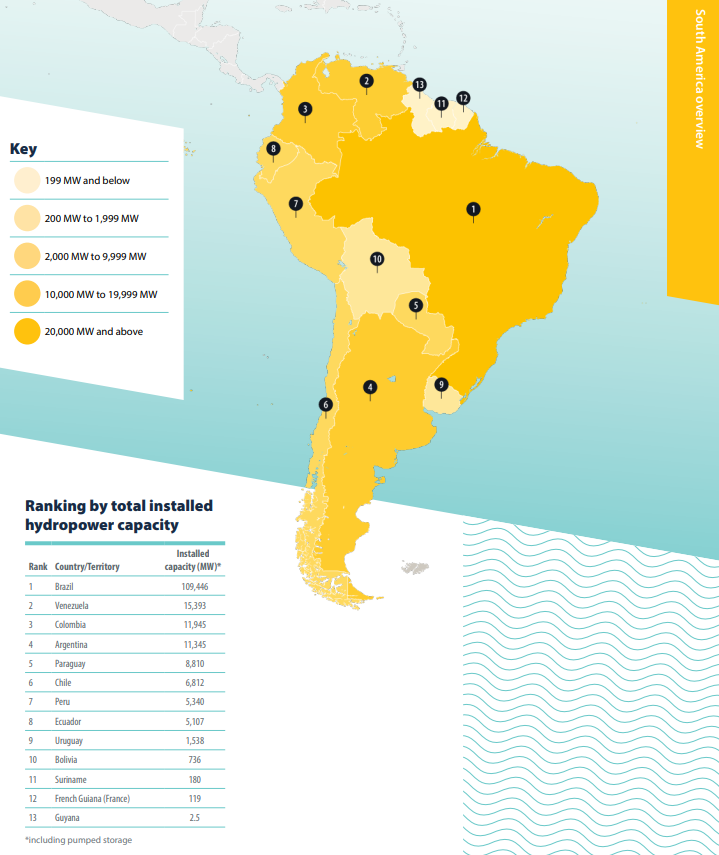

In contrast to Colorado, Concertación wants to use more of Paraguay’s hydropower resource for domestic purposes; for example, to industrialise the country. Its campaign is also focused on lowering electricity prices for citizens, with energy considered a key factor of people’s well-being. Paraguay ranks fifth in South America in terms of total installed hydropower capacity, according to the International Hydropower Association’s 2022 Hydropower Status Report.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalData

“This year, with the revision of Itaipú’s Annex C [which sets the price of Itaipu’s power] on the 50th anniversary of the treaty’s entry into force and the total amortisation of its debt – which means a 60% reduction in the cost of energy production at the dam – Itaipu’s clean and renewable energy is [firmly] on the national and regional agenda,” said Paraguayan researcher Cecilia Vuyk in an interview with Energy Monitor from Asunción, Paraguay’s capital. That is true for Brazil as much as Paraguay, she added.

The revision of Annex C is just the tip of the iceberg of a much broader management and development discussion, continued Vuyk. Last February, Itaipu Binacional paid off the last instalments of the debt contracted for the construction of the hydroelectric plant almost 50 years ago, and became an amortised company. This was “a strategic lesson” in the dysfunction of Itaipu’s current governance system, she says.

“The debt ended up costing 1,700% of its initial value, plagued by arbitrariness and corruption. The Comptroller General of the [Paraguayan] Republic in its final report of 2021 demonstrated the illegality of the debt, which, however, was paid in full by the Paraguayan government until its cancellation.” Vuyk is a member of the Itaipu ñane mba’e campaign, which wants Paraguay and Brazil to work more transparently and better together to manage Itaipu.

With better management, Itaipú could deliver more, both in energy and revenue terms, to support the development of industry, education and other priorities in Paraguay. “So far, Itaipu has worked as an oxygen tank in the form of subsidies to large multinationals in Brazil,” says Vuyk.

‘Hydroelectric sovereignty’ to beat energy poverty

Paraguay, despite being one of the largest producers and exporters of clean hydroelectric energy in South America, still consumes high levels of biomass and coal for cooking; electricity only represents 17% of the country’s total final energy consumption, and the country suffers more than others in the region from energy poverty.

While the official candidate for the incumbent Colorado Party, Santiago Peña, has been elusive in his press statements and does not mention ‘energy’ or ‘Itaipú’ in his plans, a new energy management policy is one of the central proposals of the opposition candidate, liberal Efraín Alegre.

The opposition wants to have the energy generated by Itaipu and Yacyretá – another hydroelectric dam that Paraguay shares with Argentina – channelled to improving living conditions in the country, reducing the price of energy for business, attracting investments and growing the job market.

So far, Itaipu has worked as an oxygen tank in the form of subsidies to large multinationals in Brazil.

Paraguayan researcher Cecilia Vuyk

Alegre’s platform calls says: “[We want to see] a profound change in the use of our energy that implies a transformation of the current energy model, moving from a rent-seeking policy to a true development policy, since Paraguay currently sells most of its energy […], and the benefits of such cheap energy are only reflected in the development of neighbouring countries, but not in Paraguay.”

Mercedes Canese, former deputy minister of energy and current candidate for Congress within the progressive wing of the Concertación, lays out the alliance’s hydropower vision: “[We propose to] exercise ‘hydroelectric sovereignty’ by contracting 100% of the energy from Itaipu and Yacyretá, enforcing a fair price on Brazil […], eliminating all illegal debts overpaid by Paraguay, addressing pending socio-environmental issues – such as the 38 Avá Guaraní indigenous communities affected by the construction of the dam – [and] transparent co-management [with Brazil] to control accounts and complete missing works, such as the navigation lock and dam expansion.”

Canese also foresees a 90% reduction in the National Electricity Administration company (ANDE, in Spanish) electricity tariffs paid by households in the country, helping to guarantee greater economic well-being for Paraguayan families. She calls for better grid maintenance and more electrification; for example, of transport and indigenous communities.

“Paraguay must advance with electrification of indigenous and peasant communities: according to the last census of 2017, 41% of indigenous homes did not have electricity,”said the former minister. “This is clearly ethnic discrimination and a serious case of energy poverty.”

Hydropower for green hydrogen

Plans for green hydrogen production have also landed in Paraguay, but Canese is wary, also of pressure on government to set low power prices for such an industry. “They practically do not generate employment, so they do not need to have a subsidised price,” the candidate for Congress of the opposition told Energy Monitor.

Cryptomining is similarly electro-intensive. A cryptominer can easily consume 2MW of power by employing just four people full-time. This is significant compared with other traditional industries in Paraguay such as ceramics, which consume just 0.5MW of power but employ between 50 and 200 workers.

James Spalding, former Paraguayan Ambassador to the US and general director for Paraguay to Itaipú between 2013 and 2018, sees potential for Itaipu dam to support a green hydrogen industry. “Paraguay only needs 20% of Itaipu’s energy, so [there is spare green electricity available],” says Spalding. “Having 24/7 green power is a big help in making the numbers for green hydrogen more favourable.” Itaipu’s debt cancellation in February increases the possibilities of yet more competitive prices, he adds.

Spalding is today executive director of ATOME Energy, a company on the London Stock Exchange that is fully dedicated to the development of large-scale green hydrogen and ammonia projects.

“The momentum for green hydrogen in Paraguay – and the world – is something that really […] grew from the Paris Agreement,” he says. The US Inflation Reduction Act and EU green hydrogen targets are helping to build a market for it. “Now we can have electrolysers for 20MW or more, which until recently did not exist on the market,” Spalding said on a call with Energy Monitor from Asunción.

“We are considering green hydrogen for long-distance and public transportation, as well as ammonia-powered barges. Consumers want to know what the carbon footprint of their products is, mainly ammonia for agriculture in Paraguay and Brazil. [Homegrown green hydrogen and ammonia] can help Paraguay decarbonise and alleviate the suffering of exchange rate fluctuations when importing fertilisers and hydrocarbons”, he added.

Atome’s first green hydrogen production plant is under construction in Paraguay, with a 120MW power purchase agreement signed with ANDE. Another 300MW plant closer to Itaipu is planned. The 120MW plant will produce 18,000t of green hydrogen, which Atome argues could help Paraguay and Mercosur reduce reliance on imports from faraway countries. Spalding and his team are also studying the logistics for export to Japan – which is very interested in green hydrogen and ammonia – via the Paraná Waterway or the port of Paranaguá in Brazil.

When it comes to jobs, Spalding admits that the direct jobs generated by green hydrogen production “are few” but points to a “multiplying effect” on other industries. “In Villeta there are important shipyards – Paraguay has the third-largest fleet of cargo ships in the world after China and the US – [and] there are also fertiliser and cement mixers, among other industries, with which we have already started talks,” said Spalding.

Atome is not the only founder of a green hydrogen plant in Paraguay, he added. There is already another from Canadian company NeoGreen Hydrogen too.

The future of Itaipu dam: climate risk and talks with Brazil

Scientists estimate that in 15–20 years from now the flow of the Paraná river will decline. Low rainfall in early 2022 meant that in July last year Itaipu reported that it produced 13% less energy in the first semester of 2022 compared with 2021: electricity production from January to June 2022 was 30,111GWh versus 34,535GWh for the same period in 2021.

Guillermo Achucarro, a hydrologist at the University of Montpellier, France, told Energy Monitor that since 2020, La Niña has caused changes in precipitation, affecting navigation and exports via Paraguay’s rivers. Now we are entering the ‘Zero Phase’ – a shift towards an El Niño cycle – as evidenced by recent floods in the Chaco region, he added.

“In the near future we will have either large droughts or big floods, so the water reservoir of Itaipú could begin to fluctuate,” says Achucarro. “More sovereignty of Itaipú should translate into more resources to address the multiple crises that are affecting Paraguay, including the climate crisis.”

International relations analyst Julieta Heduvan suggests that the outcome of Paraguayan-Brazilian negotiations on the Itaipu dam will depend on three main factors. “First, on the ability of the Paraguayan negotiating team to move the discussion to one between equals [and away from the existing asymmetries between the two states],” she says. “Second, Brazil’s will or need to impose itself on its neighbour, which will be closely connected to [the alignment of regional integration and national interests]. And finally, at the domestic level, the visibility [of the issue] and the pressure that local actors can exert. A lot depends on Brazil, but not everything.”