Automakers are some of the largest buyers of steel in the world. More importantly, they buy the highest grades of steel that provide the highest profit margins. So, what would happen if automakers told steel companies they no longer want dirty, coal-powered steel, and demanded clean steel to make clean electric vehicles (EVs) instead?

Clean cars need clean steel

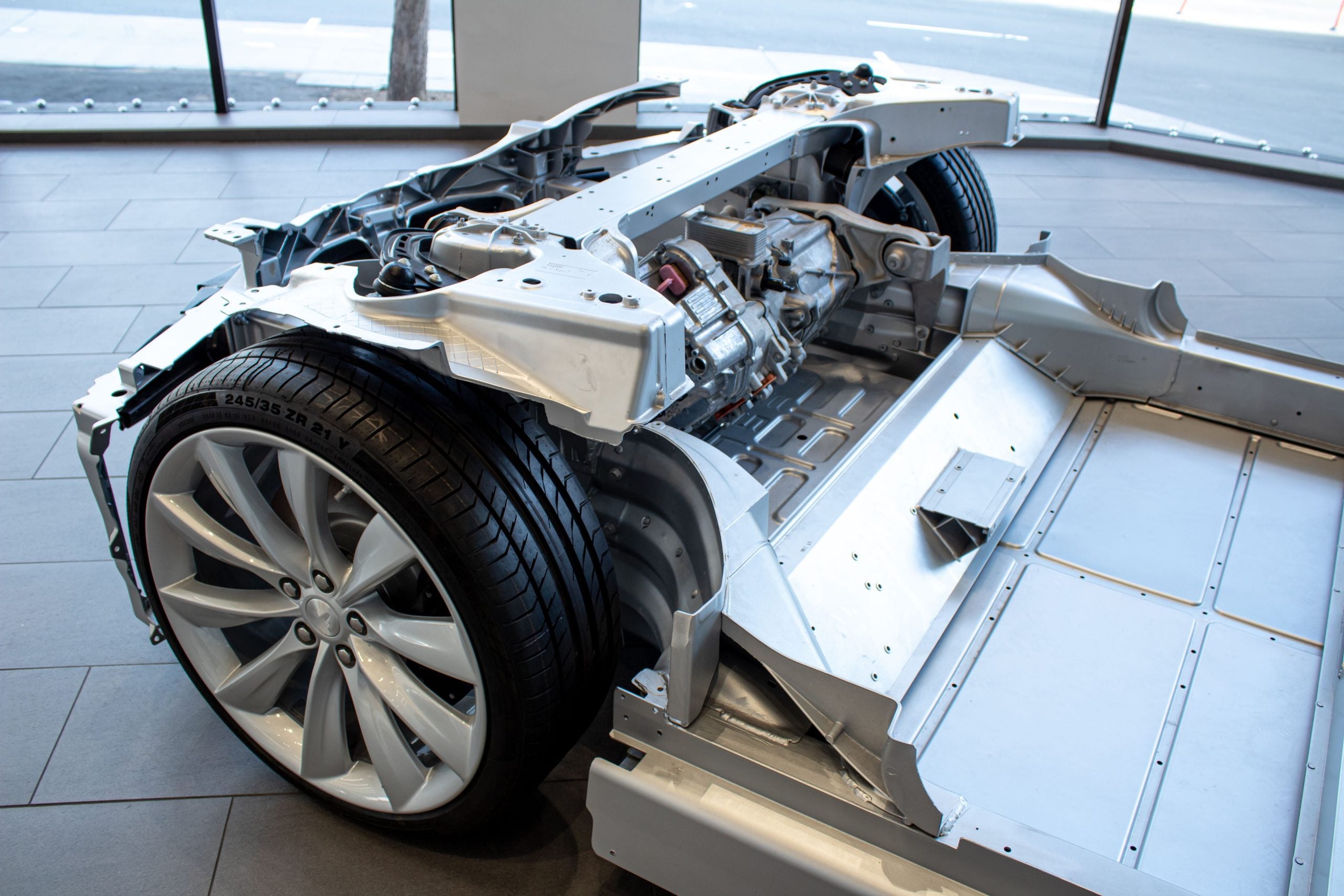

As the world shifts to EVs, the climate impact of the auto industry will no longer be defined by the petrol burned as we drive its cars but by the coal and oil embedded in the metals and other materials that make up cars in the first place. According to research commissioned by leading automakers, there is no way the industry can meet its climate commitments unless the transition to electric is accompanied by parallel, aggressive efforts to clean up its dirty supply chains, in particular steel, aluminum and batteries. The imperative to reduce embodied emissions, the growing threat of regulation and the need to differentiate amid a plethora of new electric car models in an increasingly crowded marketplace is generating pressure to act.

That pressure has led to a range of automaker announcements and supplier “agreements” on fossil-free steel. There is also the First Movers Coalition, companies committed to procuring low-carbon steel by unlocking breakthrough technologies, and SteelZero, a buyers club to build and aggregate demand and scale clean – or green – steel sector-wide. Both aim to wield their buying power as large consumer groups to help jump-start the fledgling clean steel market and generate important signals to steel makers that the demand will be there if manufacturers invest in clean steel.

There are early signs this is under way in Europe, but the current state of play doesn’t (yet) add up for steel makers to invest hundreds of millions of dollars in new clean steel facilities industry-wide. Joining these groups and establishing supplier partnerships are important steps, but many announcements lack necessary details – volume and proportion of consumption, contract duration, timing and a transparent price signal – or are non-binding memorandums of understanding (MoUs) rather than bankable contracts.

For example, GM’s agreement with ArcelorMittal appears to be a binding contract but lacks details on volume and scale. Many other agreements are MoUs or similar, such as Volvo Cars with SSAB and HYBRIT, Ford with Tata, VW with Salzgitter and BMW with HBIS. SSAB has, however, begun delivery of fossil-free steel to Volvo Trucks, which is separate from Volvo Cars, under their agreement.

What can do more to generate investment certainty are binding advance market commitments – and then future purchase, or offtake, contracts – that guarantee if steel makers invest in clean steel, automakers will buy it. Broad announcements are an important step but risk being thin; binding commitments that convert into binding contracts make investment decisions concrete.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataClean steel needs advance market commitments and contracts – that EV makers can provide

Governments have used advance market commitments to bring new technologies to market by guaranteeing demand to overcome investment uncertainty. A good example is government contracts for vaccines before they are developed to provide certainty to companies that if they invest, they will have customers.

A more recent private sector climate example is Stripe’s $1bn Frontier fund, which aims to incentivise carbon removal markets by guaranteeing a market for early stage companies. Time is of the essence for this level of ambition on steel. According to the International Energy Agency, breakthrough technologies to decarbonise the steel sector must “reach markets within the next decade”. It stresses that this “critical window of opportunity from now to 2030 should not be missed”.

With their huge purchasing power and eagerness to transition to EVs – and some already announcing initial, if insufficient, 2030 commitments – automakers are ideally placed to rise to the challenge and provide the advance market commitments needed for clean steel to become a market reality.

Keep up with Energy Monitor: Subscribe to our weekly newsletterAdvance market commitments can also be powerful tools for responsible sourcing, with the potential to strengthen environmental and human rights standards across the supply chain. Stripe‘s Frontier fund, for example, has an “environmental justice” criterion to ensure that technologies that receive funding contribute to “meaningful environmental justice outcomes via a robust process focused on local public engagement”. Advance market commitments for clean steel could drive similar outcomes by requiring, or at the very least expressing a strong preference for, clean steel produced in a way that contributes to inclusive processes and equitable outcomes for workers, indigenous peoples and local communities, from mining to manufacturing.

First-mover advantage

Advance market action is coming to automaker steel procurement. Mercedes recently announced a binding agreement to buy “50,000 tons of green steel” annually from H2 Green Steel (and broader “CO₂-reduced” steel plans in Europe and North America, as part of its ongoing partnership with H2 Green Steel). However, this is just one contract with one automaker buying a small amount of steel. We need scale in clean steel, and we need it fast.

Sending strong demand signals to the market is essential for this to happen. Joining SteelZero and the First Movers Coalition is a critical first step for steel buyers as members of these groups set purchasing targets for clean steel. Joining think tank RMI’s newly launched Sustainable Steel Purchasing Platform would also unlock the power of aggregated demand across multiple buyers. However, major buyers such as automakers need to go a step further and make binding advance market commitments with specific amounts of funding and/or volumes for clean steel from facilities that are yet to be converted or even built. Such commitments would dramatically change the market by generating certainty and establish the basis for binding contracts.

Now is a unique moment to act because of generous subsidies available to steel mills to upgrade their facilities in key markets. In the US, the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) has $5.8bn in incentives that can be tapped for clean steel and a whopping $50bn is available in Germany for heavy industry decarbonisation. Similar incentives may follow in major East Asian steelmaking countries such as Korea. If a steel company has guaranteed demand from its biggest customers, with billions in potential incentives to help cover a green premium, the equation quickly flips. Instead of investment uncertainty, they face competitive uncertainty – will they lose those customers if they fail to invest in clean steel?

The same is true for automakers because there is a clear first-mover advantage here. Each year, the auto sector accounts for 27 million tonnes of consumption of steel in the US, 28 million tonnes in the EU and 60 million tonnes in China, but “demand will likely exceed the supply of low-CO₂ steel in the near future”. Atop that, by 2030, EVs alone are projected to demand eight million tonnes of clean steel – nearly half of what could be available.

“Near-zero emissions steel demand… will reach 6.7 [million tonnes]” and the “automotive sector will represent half”, according to a new RMI study on the US market. That means the first automakers to lock in clean steel supply with advance market contracts – and high responsible sourcing standards – would have a significant competitive advantage in a crowded market: clean cars that help bring clean steel and clean jobs. That’s an EV ad that practically writes itself.

Getting the steel industry on the 1.5°C track requires a lot of action, and it needs it now. We already have early auto movers on clean steel – but now we need to scale at speed. Growing advance market commitment announcements can send the market signal required to scale; working with steelmakers to convert these commitments into binding contracts can generate the speed. Just two of the “right conditions” clean steel needs and the opportunity for automakers is there for the taking.

Authors' note: The term “clean steel” is used interchangeably with "green steel" to mean made “without the use of fossil fuels” and with additional high responsible sourcing standards.

About the authors: Mat McDermid is the programme director for the automotive sector, including the electric transition and supply chains, at the Sunrise Project. He has more than a decade of experience in corporate sustainability, environmental and social impact, and campaigning.

Justin Guay is the director for global climate strategy at the Sunrise Project. He has a decade of experience in nonprofit advocacy and foundation strategy development.

Hilary Lewis is the steel director at Industrious Labs, an advocacy organisation dedicated to decarbonising heavy industry.

Chris Alford is the senior strategist for auto supply chains at the Sunrise Project. He has more than a decade of experience leading campaigns for social and environmental justice across Latin America.