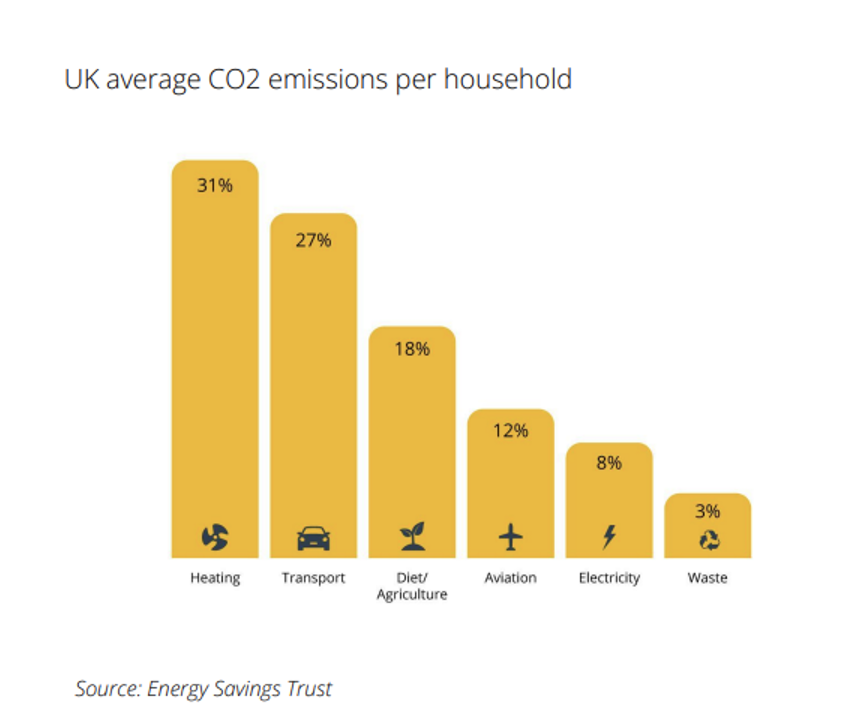

Household heating is the source of 17% of the UK’s carbon emissions. Most of the country’s homes are still heated by fossil fuel boilers, and heating is also the leading source of the average UK household’s emissions, ahead of daily transport, diet, flying, electricity and waste. However, while other sectors are fast decarbonising, household heating emissions remain stubbornly high, and the country now has just 27 years to decarbonise 27 million households.

However, in its novel Zero Emission Boiler (ZEB), Wokingham-based start-up tepeo believes it holds part of the solution. As my Uber drove me out to visit their headquarters recently, traversing the bleak suburbs of the despairingly practical London commuter town that is Reading, it was easy to imagine I was on the way to The Office to meet David Brent and the gang. To my surprise, I arrived at a rather smart industrial estate and was ushered into a state-of-the-art 9,000ft² office-cum-factory where tepeo produces and markets the ZEB. This innovative piece of cleantech, essentially a miniature thermal energy battery for your house, has been designed to be a simple and affordable replacement for fossil fuel boilers.

The ZEB was recently nominated as a finalist in the prestigious Ashden Awards, a UK-based awards ceremony celebrating world-leading climate solutions. “Tepeo are bringing new options to UK homes to electrify heating,” says Stephen Hall, head of awards at Ashden. “We know we need to move millions of homes to electric heating by 2030, and tepeo’s Zero Emission Boiler means people can switch their heating to electric in as little as two days, with minimal disruption – they can even keep their existing radiators! Having new options for clean heating like this is an important step on the UK journey to net zero and warmer homes.”

The Zero Emission Boiler: a low-carbon alternative to heat pumps

Tepeo was founded in 2018 and launched the ZEB in 2021. In its first five years, the company has grown to 55 employees and raised more than £15m ($18.63m) in funding. Sales of the ZEB started last year and are still “in their hundreds”, according to tepeo’s founder and CEO, Johan du Plessis.

The ZEB is designed to offer an alternative to heat pumps. Although a key climate solution in their own right, heat pumps can be complicated and disruptive to install, and require installation skills that are still thin on the ground in most countries. They also need varying amounts of outdoor space.

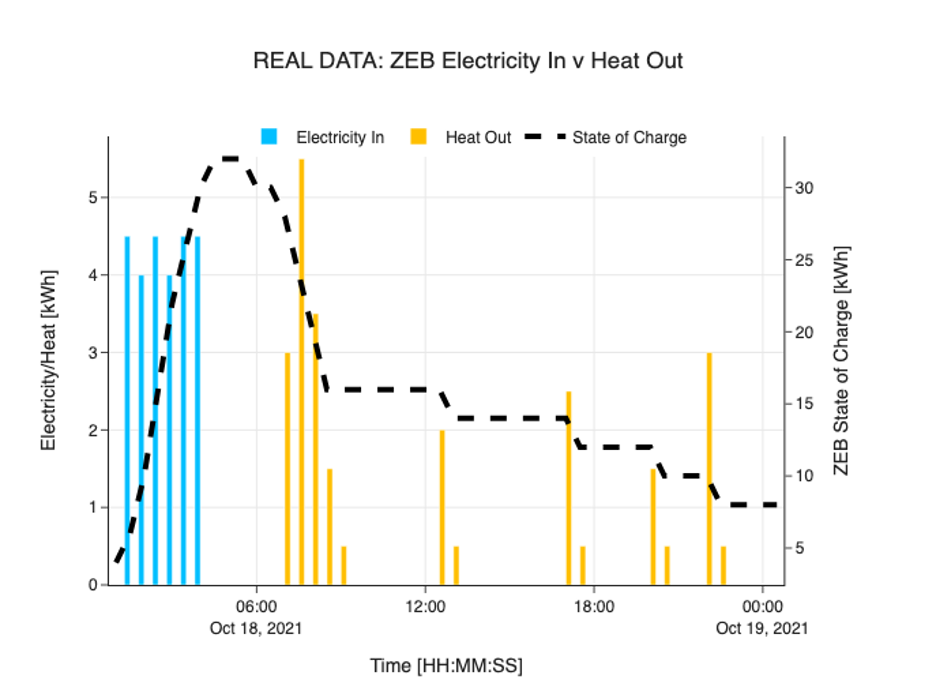

In contrast, the ZEB is designed to be a low-carbon plug-and-play replacement for fossil fuel boilers that is able to use a household’s existing heating infrastructure. It is powered by electricity and works like a battery to store energy as heat until it is needed. Electric heating elements charge up a “core” inside the ZEB. Its heat-management technology then releases the heat to the household’s radiators, underfloor heating and water tank when the thermostat calls for it.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalData

Tepeo’s smart charging algorithm works out when and how much to charge the boiler to keep running costs and carbon intensity as low as possible. Using machine learning, the ZEB calculates a household’s energy demand and uses the local weather forecast to predict that demand for the coming day. The boiler then estimates how much to charge, and when, according to the household’s tariff pricing plan, grid carbon intensity and predicted heat demand. It makes adjustments in real time throughout the day.

Recent analysis commissioned by Danish energy giant Danfoss revealed that an ambitious but realistic roll-out of such technology in Europe (the EU and UK) could save 40 million tonnes of CO₂ emissions each year by 2030, more than Denmark’s domestic climate footprint. Additionally, Europe could achieve an annual societal cost saving of €10.5bn ($11.42bn) by 2030 and €15.5bn by 2050. These savings would pay for most of the costs of rolling out such demand-side flexibility infrastructure.

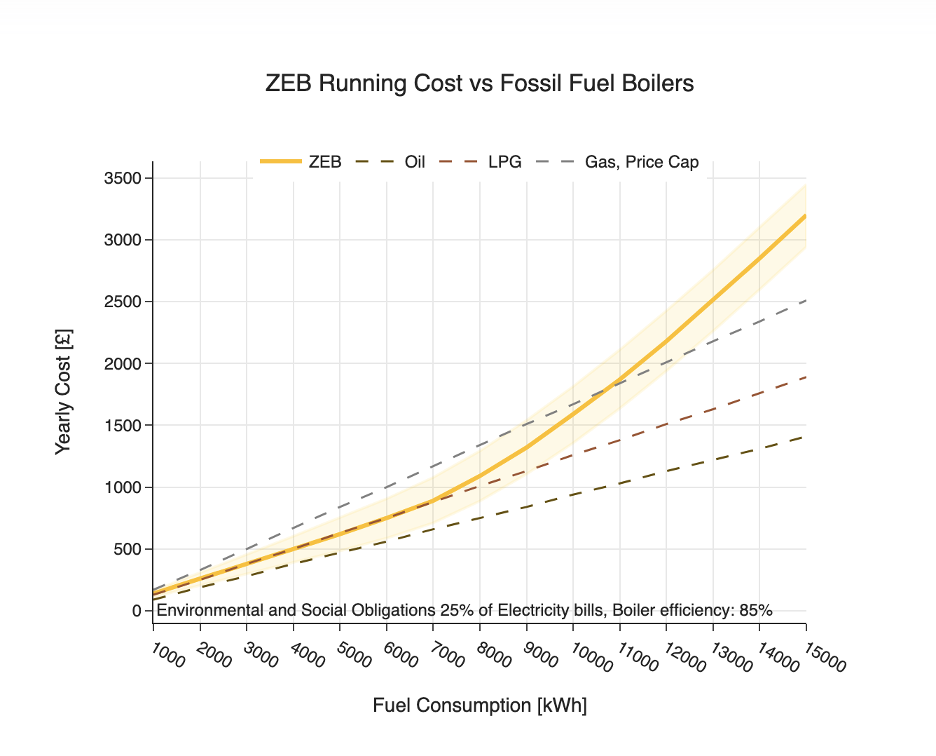

Peak power prices can sometimes be four to five times more than off-peak prices. This means that even if electricity prices are higher than gas prices, the ZEB can still be relatively cost-comparable to a gas boiler. All-in, the ZEB costs £8,000 to buy and install. That compares with £4,000 for a typical gas boiler and up to £15,000 for an air source heat pump – although subsidies provided by the UK Government bring the latter down to around £5,000 (and Octopus Energy recently launched a £3,000 heat pump). A ground-source heat pump, however, costs between £18,000 and £50,000 to install and requires considerably more outdoor space than its air-source counterpart – despite boasting much more favourable running costs.

Indeed, in its running costs, the ZEB is also comparable with air source heat pumps and gas boilers. The ZEB will cost around £734 a year to run compared with £1,917 for a direct electric boiler, £679 for a gas boiler, £799 for a high-temperature heat pump and £701 for a low-temperature heat pump, tepeo estimates.

“Clearly it is a lot better than just an electric boiler, given that electricity prices are 3.9 times more than gas right now,” says Jan Rosenow, principal and director of European programmes at the non-profit Regulatory Assistance Project, and one of the world’s leading authorities on energy efficiency. “I haven’t been able to investigate tepeo’s modelling but I would [however] be surprised if you will be ever able to find a case where it is actually cheaper to heat with a tepeo boiler than a gas boiler.”

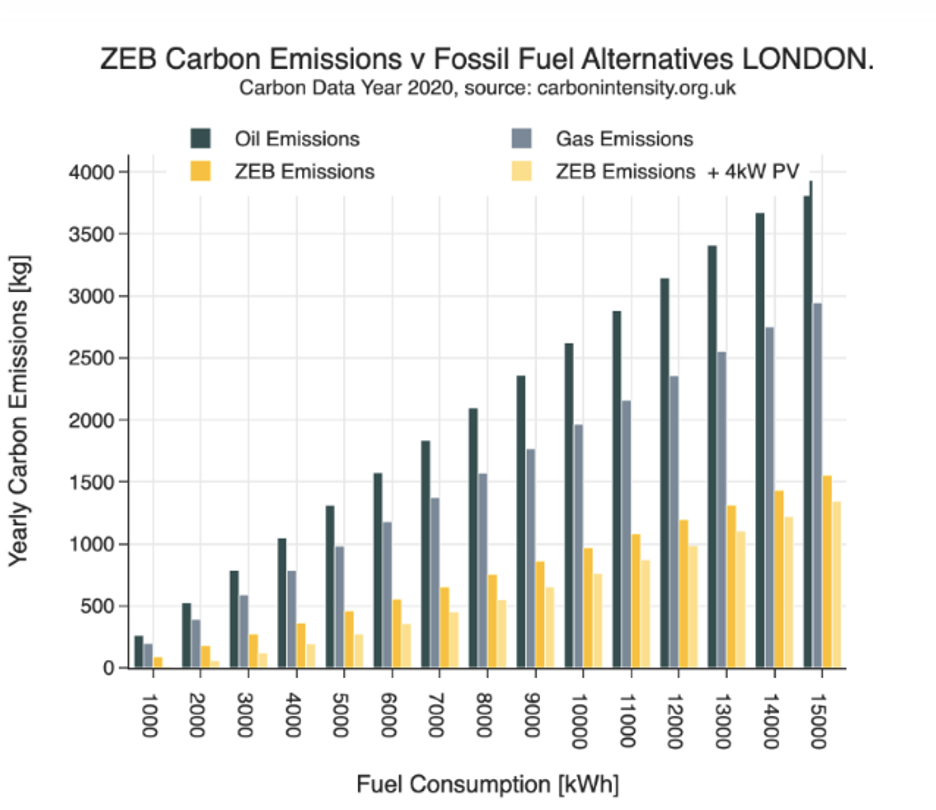

Although the gas boiler remains the cheapest to install and run, the ZEB is cleaner. It will save 2 tonnes of CO₂ each year – the equivalent of driving 15,000 miles in a diesel car – for a UK household using 12,000 kilowatt-hours (KWh) annually, according to an independent assessment from Dutch climate consultancy Impact-Forecast. Those carbon savings will only get larger as the UK grid decarbonises.

The ZEB also uses low-impact and long-lasting materials. Its core is made of magnetite, a common iron ore that degrades slowly and is easily recyclable. Although the machine has a ten-year warranty, it is built to last more than 20 years, according to du Plessis.

“Heat pumps are appropriate for most homes in the UK, but it depends on how much upheaval people are willing to put up with and the cost of doing so,” says du Plessis. “Probably the strongest case for ZEBs is in places where there isn’t the outdoor space to install an air or ground source heat pump, such as flats and mid-terrace houses. Without a solution like the Zero Emission Boiler, there really isn’t another option for those people to decarbonise their heating.”

Heat pumps “not the only show in town”

Nonetheless, the ZEB is still considerably more expensive to buy and install than an air-source heat pump. Air source heat pumps have access to up to £10,000 in government subsidies (£7,500 upfront, plus VAT exemption of £2,500) that can bring their all-in cost down from £15,000 to just £5,000 – compared with £8,000 for the ZEB.

The recent update to the Boiler Upgrade Scheme has seen the UK’s upfront subsidy rise from £5,000 to £7,500 for heat pumps. If the ZEB was eligible for one-third of the capital support given to heat pump installations – £2,500 – it could be installed and run for the same cost as a typical replacement gas boiler, while saving an average of 344kg of CO₂-equivalent (CO₂e) per year today, and more than 1,000kg of CO₂e each year by 2030, according to tepeo.

This could be an important shot in the arm for the UK’s low-carbon heating plans. The government wants to end the installation of replacement gas boilers in 2035 (albeit with enduring exemptions for up to a fifth of homes). It also has an ambitious target to install 600,000 heat pumps a year by 2028; however, only 72,000 were installed in 2022. Tepeo argues that if ZEBs were included in the Boiler Upgrade Scheme, the UK could decarbonise three-times as many homes with the same amount of funding. By 2028, 10% of home installs could be ZEBs, tepeo suggests.

“The government must remember that heat pumps, while suitable for some properties, are not the only decarbonised heating products on the market,” says du Plessis. “They must take a broader approach to heating and encourage the consumer to choose a gas boiler-alternative that works for them. Heat pumps are not the only show in town.”

Aiming for a quarter of UK households

Overall, the ZEB is an exciting new entrant to what is a fairly limited market for low-carbon heating solutions. It is well suited to the average heat demand of flats, terraces or semi-detached properties, with tepeo estimating its addressable market in the UK at around 40% of homes. Its ideal market is homes that use 3,000–12,000kWh of energy per year for heating and hot water (roughly 1,100 litres of oil), have a ‘wet’ heating system (radiators or underfloor heating), a hot water tank and sufficient space on the ground floor to fit the machine.

Heat pumps will be the most appropriate low-carbon option for most UK homes. However, the UK’s net-zero transition will need a range of solutions, suitable for different property types, and the ZEB could represent a part of that mix. Du Plessis forecasts that if the market is allowed to run its course, the UK’s home heating mix will eventually comprise around 60% heat pumps, 25% thermal storage solutions like ZEBs and 15% heat networks (district heating).

“Purists will say that heat pumps can work in every house, in every building – and yeah, they can in theory – but you have to overcome all the practical elements: the space constraints, the upheaval required for the consumer, the behavioural change from the consumer, [and] the skills needed to get the thing installed,” says du Plessis. “With a Zero Emission Boiler, you can compete on running costs, you can massively reduce the carbon intensity of the energy you are consuming by being flexible about when you use it, and you can do it now.”

Rosenow agrees that for properties where it will be difficult to apply heat pumps or district heating, electric boilers like tepeo’s could play a role; particularly with highly efficient buildings, where the heat demand is typically low. “I would have thought that is a pretty good fit,” he says.

However, he questions whether the ZEB will ever gain widespread adoption given that the running costs will always be significantly higher compared with any heat pump system because of the difference in efficiency. “You need about three times as much electricity when you use an electric boiler compared to a heat pump,” he says. “Granted, I haven’t had a chance to investigate tepeo’s offering yet, but I just don’t see how that side would stack up.

“It could play a role, but it is yet to be seen to what extent it can compete economically with other proven technologies,” he concludes.