Europeans this summer have been presented with a disjointed reality on their newspaper front pages. On one side, they have read stories about global heat records, wildfires and floods, which few nowadays deny are being spurred and worsened by man-made climate change. Yet, on the other side of the front page, they are reading stories about their leaders walking back their climate commitments, thinking that opposing climate efforts will be a winner at the ballot box.

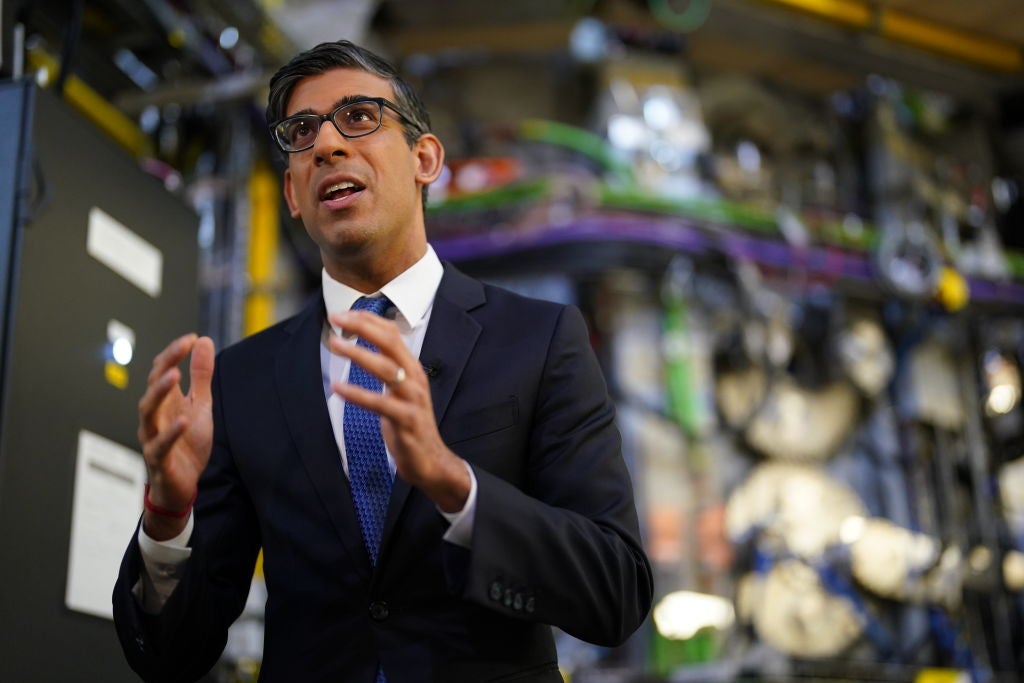

In the most recent example, British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak announced last week a plan to “max out” the UK’s oil and gas reserves with a no-holds-barred push for new North Sea drilling, authorising 100 new licences. It came a week after he declared war on British laws designed to encourage a modal shift from cars to public transport or cycling. He said he will review “anti-car schemes across the country” such as low-emission zones, cycling infrastructure and low speed limits.

Meanwhile, in Brussels, the centre-right European Peoples Party (EPP), under the leadership of German conservative Manfred Weber, has decided to take on one of its own, conservative European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, over what it calls overburdensome climate legislation. Weber spearheaded his pan-European group’s opposition to a central pillar of von der Leyen’s green deal, the EU Nature Restoration Law, in the European Parliament.

That attempt to kill the law was narrowly defeated by an alliance of the left, Greens, Liberals and some EPP defectors. However, the language used during the debate signalled that Weber intends for the EPP to campaign on a promise to “rebalance” Europe’s climate policy amid concern that the EU is being far “more ambitious” than the rest of the world. While Weber has insisted that the EPP still believes that “climate change is the biggest challenge of our generation”, the group’s shift suggests they will use opposition to climate laws seen as overburdensome on the campaign trail in the EU elections next June, seeing it as a vote winner. The pressure on von der Leyen looks likely to make her hold back a proposal for a new 2040 climate target, especially now that her vice-president for the green deal, Frans Timmermans, is leaving to run to become Dutch prime minister.

Keep up with Energy Monitor: Subscribe to our weekly newsletterIn Italy last month, as unprecedented wildfires raged in Sicily, far-right Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni told a rally of Spain’s far-right Vox party that “ultra-ecological fanaticism” was a threat to the economy. Her transport minister said of the summer’s extreme weather, “In summer it is hot, in winter it is cold”. Her environment minister said he wasn’t sure if climate change is caused by man.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataEach summer, Europe and the US break new heat records. This summer saw the hottest June ever in Europe, with new maximum temperature records being set across the South. A report from non-profit news organisation Climate Central this month concludes human-caused climate change spurred these extremes, using a tool called the Climate Shift Index. “At least two billion people [a quarter of the Earth’s population] felt a very strong influence of climate change on each of the 31 days in July,” the report concludes.

So why the disconnect? Why, when the effects of climate change are hitting home more than ever for Europeans, are politicians here thinking that enacting efforts to combat climate change won’t win them votes? Are they right?

Politicians don’t make these calls in a vacuum. They are looking at internal and external polling, as well as the recent success of far-right populist parties that have campaigned on anti-climate-policy platforms. There is also climate fatigue. As people hear each summer that new records are being set because of climate-induced extreme weather, there may paradoxically be less and less impetus to act.

Over the past three years, the consecutive summers of extreme weather don’t seem to have directly led to a push for further climate action. The Inflation Reduction Act in the US had to be disguised as something else – an economic recovery measure – in order to pass, even after the extreme US weather of 2021 and 2022.

A Eurobarometre survey published in June found that even after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, climate change remains among the top three concerns of Europeans. Of EU citizens, 93% believe climate change is a serious problem, 88% support the EU reducing its emissions to reach net zero by 2050 and 67% think their governments are not doing enough to tackle climate change.

Read more from this author: Dave KeatingFrom these figures, it sounds like governments combatting climate change should be a no-brainer. However, a more nuanced survey of Europeans by YouGov published in May found an important caveat – when asked about specific policy initiatives, Europeans were less likely to support them if they had a personal impact on their lives. For instance, only 30% of people supported phasing out internal combustion engines.

It should be the job of politicians to explain to citizens why policies that may involve an element of personal sacrifice in the short term will pay off in the long term – but politicians are rarely known to prioritise long-term over short term-thinking. Next year will bring a series of key elections, most importantly the EU election and the UK election, which will determine whether these strategies by Europe’s centre-right will pay off with voters.

Citizens should be aware that if they support parties that demonise specific climate policies (even while vaguely supporting the principle of climate action at a high level), they are sending a message to politicians that they don’t want them to act on climate change. It may be that voters themselves aren’t understanding how their election choices may be inconsistent with their horror as they see the extreme weather events unfolding because of climate change. That is why it will be key in these upcoming elections to explain why, while the message of ‘overburdensome climate legislation’ may seem appealing, supporting such rhetoric will mean these extreme weather events will only get worse.

About the author: Senior writer Dave Keating is a US journalist and conference moderator covering European affairs from Brussels, with a focus on environment and energy. He has worked for France24 and Forbes. Contact Dave at: dave.keating@energymonitor.ai