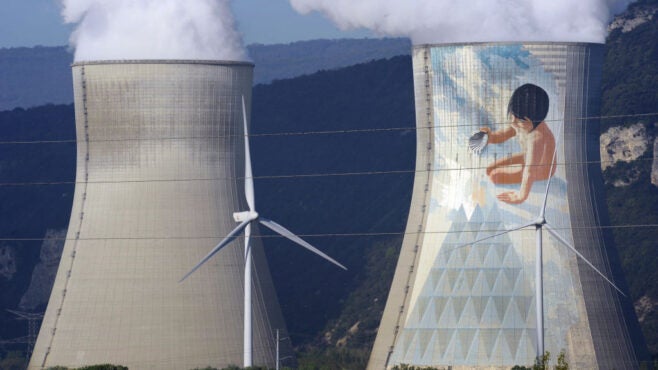

In a world aiming to be carbon neutral, France appears to be a winner. Its electricity-related CO2 emissions are extremely low because most of its power comes from nuclear plants. Its citizens also enjoy some of the cheapest electricity in Europe. However, the country is at a critical juncture. Its nuclear reactors are old and the government is under increasing pressure to invest in renewables rather than new nuclear, but moving towards a 100% renewable system poses its own challenges.

Ultimately, massively ramping up renewables while investing in the research and development of new technologies, including in the nuclear space, is likely to be the best option, but this is a decision that will likely only be made after the 2022 presidential elections.

About 70% of France’s electricity comes from nuclear energy. In 2019, the average emission factor of electricity generation was 35 grams of CO2 a kilowatt-hour – 11 times less than Germany. Household consumers in France pay on average 40% less per kilowatt-hour than their neighbours – but this reality is changing. The government foresees nuclear’s share in the electricity mix falling to 50% by 2035 and many energy experts believe it is high time France ditched nuclear in favour of renewables.

“People talk about nuclear as if the facts don’t matter,” says Mycle Schneider, Paris-based energy consultant and lead author and publisher of the annual World Nuclear Industry Status Report (WNISR). The latest edition reveals a global trend away from nuclear with non-hydro renewables generating more electricity worldwide than nuclear for the first time in 2019. This tendency is valid for France, says the report, which shows nuclear plants generating 3.5% less power in 2019 than the year before, its lowest share in 30 years.

How well do you really know your competitors?

Access the most comprehensive Company Profiles on the market, powered by GlobalData. Save hours of research. Gain competitive edge.

Thank you!

Your download email will arrive shortly

Not ready to buy yet? Download a free sample

We are confident about the unique quality of our Company Profiles. However, we want you to make the most beneficial decision for your business, so we offer a free sample that you can download by submitting the below form

By GlobalDataPart of this fall is due to an increasing number of reactors suffering complete capacity outages and “many days when reactors have low production”, says the report. A key problem is that France’s nuclear reactors are old. By mid-2020, the average age of France’s 56 nuclear reactors exceeded 35 years. A programme is under way to extend their lifetime past 40 years, out to 50 or even 60 years, but this still means the vast majority will be need to be decommissioned between 2030 and 2050.

At the same time, renewable energy is slowly, but surely, increasing its share in the country’s power mix.

France’s energy and climate law came into being in November 2019. As well as maintaining a target to reduce nuclear’s share in the electricity mix to 50% – though pushing it back by ten years – it sets clear renewables goals and ups the stakes on phasing out fossil fuels.

By 2030, renewable energy is expected to reach at least 33% in gross final energy consumption and 40% in electricity production. That is more than twice its contribution to electricity production in 2019, which was 17%. In addition, by 2030, fossil fuels should make up no more than 40% of the energy mix, with the last coal-fired power plant scheduled to close by 2022.

Money, money, money

Based purely on economics, renewables trump nuclear and could take an 85% share in the country’s electricity mix by 2050 and over 95% by 2060, concludes a study published by Ademe, France’s energy transition agency.

“Nuclear is expensive,” underlines Schneider, citing the falling costs of solar and wind power, and storage. “Nuclear will never be competitive and it is questionable how long we can keep the old plants running. Building new nuclear is making the climate crisis worse as capital is diverted from cheaper and faster options to reduce emissions.”

Behrang Shirizadeh, a researcher who recently received his PhD from France’s International Centre for Research on the Environment and Development, has carried out detailed modelling around the costs of nuclear and renewables. He is convinced going all-out for renewables is the most cost-efficient option for France, providing electricity that is cheaper than or equal to the current system.

Shirizadeh insists that investing in a plethora of renewable technologies, from wind and solar power, to hydropower, pumped storage, green hydrogen, methanation, power-to-x, biogas and batteries, is preferable to spending time and money on new nuclear.

Ademe believes that a progressive increase in the share of renewables will actually bring down the cost of electricity billed to consumers, pushing it towards €90 a megawatt-hour (MWh), excluding tax, compared with close to €100/MWh currently. It also notes that reducing demand for power, notably through energy efficiency “would lead to a 7% reduction in the total cost of the system and a 22% reduction in CO2 emissions in 2060 while still allowing an increase in [electricity] exports”.

On the other hand, from an economic point of view, developing a new-generation nuclear power industry “is not cost-effective for the French electric power system”, says Ademe. Building an EPR in 2030 would require public support of €4–6bn. Over the longer term, the additional cost of developing the industry around the EPR would cost the nation at least €39bn.

Big business

At the heart of the energy debate in France is Électricité de France (EDF). Founded in 1946 with the nationalisation of around 1,700 smaller energy producers, transporters and distributors, EDF became the country’s premier electricity generation and distribution company. Its monopoly ended in 1999 when EU legislation forced it to open up 20% of its business to competitors. Nonetheless, it remained state-owned until 2004, when it became a limited-liability corporation. The French government retains an 84% stake in the company.

Building new nuclear is making the climate crisis worse as capital is diverted from cheaper and faster options to reduce emissions. Mycle Schneider, WNISR

Given EDF’s net financial debt, which increased by €8bn in 2019 and another €1bn in the first half of 2020, the only way new reactors could be built is with public support, says the WNISR. Such a move would only be acceptable if nuclear energy were “sufficiently competitive” vis-à-vis other sources to deliver national climate objectives and security of supply.

Nuclear is EDF’s bread and butter and despite the group’s increasing focus on renewables, it continues to insist new nuclear is necessary for the energy transition in France.

“We must not be ideological and take for granted we know all the solutions that will lead us to climate neutrality by 2050,” says Erkki Maillard, senior vice-president for European and international affairs at EDF, and adviser to the company’s chairman and CEO, Jean-Bernard Levy. “We need to look at this in a humble way. Lots of developments can happen. We need all the low-carbon technologies available.”

He forecasts a “steep rise” in renewables in France, but remains unconvinced wind and solar can manage the job of decarbonising the energy system on their own. “The more renewables, the more dispatchable capacity, such as nuclear, you need to get renewables into the grid,” he claims. “Our objective is to reach a balance of renewables and nuclear.” Given this assumption, he believes: “It is not a question of whether we will need nuclear, but what will be the size of the nuclear fleet.”

Maillard continues: “We have to compare what is comparable.” He insists nuclear can be relied on day and night, while renewables cannot. Any cost comparison between technologies is difficult, he adds, because they do not compare like-for-like and the price of renewables should include grid costs. “I am not saying a 100% renewables system is not possible,” says Maillard. “It may be feasible under several social acceptance and economic constraints.”

Schneider dismisses the idea that nuclear plants can provide power 24/7. “Nuclear is the least flexible electricity source and incredibly unreliable,” he says. As for arguments around the “intermittency” of solar and wind, “I am pretty sure the sun goes up every morning”, and meteorological models today can reliably predict the availability of solar and wind,” says Schneider.

Eyes on the prize

Staying focused on the goal of net zero rather than arguing over technologies is critical for Nicolas Berghmans at the Institute for Sustainable Development and International Relations, a Paris-based think tank. “We might have to invest in everything [to keep our technology options open],” he says.

If decisions are taken without proper thought there will be “large inefficiencies”, he warns, urging plans to take full account of the potential for energy efficiency improvements.

In Berghmans’ view, the cost difference is “not that big” between a renewables-based system and one with some nuclear in it. While there are big questions surrounding nuclear, renewables face challenges of their own, he insists. “We can’t put wind energy everywhere and we need to invest in the network if we go for renewables,” he says. “We need to make decisions that are based on much more than just the cost of production.”

“We might have to invest in everything to keep our technology options open.” Nicolas Berghmans, IDDRI

Mike Hogan, senior advisor at the Regulatory Assistance Project, a not-for-profit, agrees. “There is no point in glossing over the challenges presented by wind and solar,” he says. “What is needed are things like modular turbines, high-speed diesel plants capable of burning hydrogen, and flexible demand. Yes, wind and solar are very predictable hours or a day or two in advance, but the 95% confidence interval for what wind production will be on 11 March 2022 is far wider than it is for these other options.”

Hogan, like many of his peers, also disputes the idea of nuclear as a “flexible” solution. “We should keep at least some existing nuclear plants running until we can replace their production with other zero-carbon energy, but that is really the only reason,” says Hogan. “We will need zero-carbon dispatchable resources to ‘get more renewables into the grid’, but the key is that they are flexible. The costs of operating nuclear plants flexibly enough [to help balance wind and solar power] can be seen in the high outage rates and shortened component lives of France’s nuclear fleet.”

France built a large amount of pumped storage hydro and a network of thermal storage facilities precisely because the existing nuclear is not flexible in any practical sense, he adds.

In a joint study, the International Energy Agency and France’s transmission system operator, RTE, conclude it is technically feasible for the country’s power system to be based on very high shares of renewables if various criteria are met, not least the availability of “substantial sources of flexibility”. They suggest “demand-response, large-scale storage, peak generation units and well-developed transmission networks and interconnections” as possibilities.

A high-renewables scenario would also mean substantially revising the regulatory framework for balancing responsibilities, continually improving forecasting methods for renewables, and carrying out “substantial grid development efforts”, says the study. RTE will publish a full assessment later this year of different power system scenarios that could take France to carbon neutrality.

Ill-fated Flamanville

One of the reasons the debate around nuclear is so heated in France is because the only recent project is the infamous Flamanville-3 EPR. It is at least ten years behind schedule and costs have soared. The latest estimates put its price tag at €12.5bn, up from €2.5bn at the outset. A damning report by the country’s Court of Accounts slams a lack of government oversight. The reactor is now supposed to be fully online by the end of 2022 at the earliest.

“We had to adapt to changes to technical references and this led to higher costs and delays,” says Maillard. “And France didn’t build any nuclear power stations for more than a decade, leading to the loss of companies and qualifications and making it difficult to secure the right workforce.”

[Keep up with Energy Monitor: Subscribe to our weekly newsletter]

However, there is no reason why issues encountered at Flamanville would be replicated elsewhere, he insists. “Flamanville was the first of this kind of EPR to be built,” he says, pointing to reactors now using similar technology in China, which he says are “working well and at full capacity”.

Hogan suggests the situation is not quite so simple. “Flamanville is not the only EPR to go completely off the rails,” he says, also citing two ‘next generation’ nuclear plants in the US. “Areva’s Olkiluoto 3 in Finland has been at least as much of a disaster and Hinkley Point C in the UK is looking like it may be much the same,” he adds.

Hogan also dismisses the idea that costs for existing nuclear technologies are likely to fall. “The learning curve argument for traditional nuclear plants has never been borne out in practice,” says Hogan. “No one really knows what the existing French nuclear plants have cost taxpayers and consumers, with costs like the need for large storage facilities or decommissioning buried in other accounts or ignored altogether. It makes sense to pursue new concepts like small modular reactors, but those are many years away at any meaningful scale.”

Climate neutrality

EDF is preparing a report for the French government on how it sees the future of the country’s energy system, including the cost of nuclear, for the end of the year. However, no decision is likely to be made on whether to build any new reactors until after the 2022 French elections.

The government also needs to decide what to do with EDF itself. The company has mooted plans to separate its debt-laden nuclear power arm from the rest of the company’s assets to unblock investment, including in renewables. Trade unions are firmly opposed to the plans, concerned it could lead to a break-up of the group. The European Commission does not believe such a move would solve its concerns around compliance with anti-trust and state aid law.

Then there is the question of jobs. Nuclear is France’s third-largest employer, after the aerospace and automotive industries. It provides 220,000 jobs, compared with 152,000 in the renewables sector in 2019. Going forward, however, the local economic impact and job creation potential is better for renewables than nuclear, argues Zélie Victor, a policy advisor with NGO Climate Action Network. The renewables sector could supply the equivalent of 264,000 jobs by 2028, forecasts French renewables trade association SER.

“All reasonable options should be on the table as we debate how to rapidly decarbonise our economy while continuing to meet society’s demand for energy,” writes Michael E Mann in his recently published book The New Climate War. “There is no easy solution, and there are important and worthy debates to be had in the policy arena as to how we accomplish this challenging task.”

These debates need to be based on facts, technological and economic, with a firm eye on the prize of climate neutrality.

Energy Monitor is publishing a series of articles about nuclear power and the energy transition to mark the tenth anniversary of the Fukushima Daiichi disaster in Japan. The earthquake and tsunami led to a sea change in the role of nuclear power around the world. In Japan, nuclear plants made up less than 5% of the electricity mix last year, down from 30% before Fukushima. In Germany, the accident led to the immediate shutdown of eight nuclear plants and the definitive decision to exit nuclear power entirely by 2022. Ten years later, as countries face up to the climate crisis, Energy Monitor examines the role of nuclear power in the energy transitions in Japan, the US, China, France and the EU.

Other articles in this series:

- A decade after Fukushima, Japan still struggles with its energy future

- Will there be a second act for the US nuclear power industry?

- Will China gamble on a nuclear future?

- Brexit may tip the scales towards an EU nuclear phase-out