On 9 January, UN secretary-general António Guterres and Pakistan’s Prime Minister, Shehbaz Sharif, held a conference in Geneva looking to raise an eye-watering $16bn to help the South Asian nation recover from last year’s devastating floods.

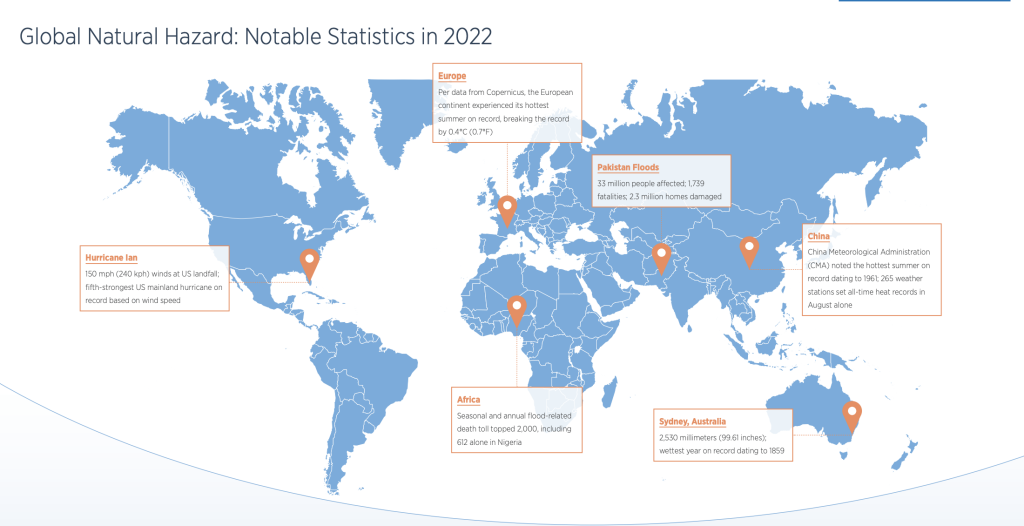

All over the world, climate change is making such natural disasters more frequent and more severe. Along with Hurricane Ian in the US and floods in Australia, Pakistan’s inundation helped make 2022 one of the costliest on record for climate disasters; weather events intensified by climate change resulted in a direct economic cost of $360bn, according to reinsurance broker Gallagher Re.

However, there is growing acknowledgement that the traditional humanitarian response to these events is no longer fit for purpose. Many in the aid sector are pushing the idea of acting earlier, leveraging technological advances and existing solutions to forecast, plan for and respond to natural hazards before they become catastrophes. “If we act early, we act smart,” says Mami Mizutori, special representative of the secretary-general for disaster risk reduction at the UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction.

“Anticipatory action” forecasts the potential impact of disasters using science and data to trigger pre-determined humanitarian actions aimed at protecting vulnerable communities from the likes of displacement, disease and livelihood loss before they reach crisis levels.

However, anticipatory action requires funding at scale, and there is one burgeoning financial instrument that could tap not only traditional aid budgets but also the growing swell of philanthropic and private climate finance that is steadily flowing into climate adaptation: anticipatory insurance.

“For those large-scale disasters”

In November 2022, Senegal demonstrated exactly what anticipatory insurance is all about: the government received $400,500 in insurance payments from aid organisations. The insurance, taken out by the Start Network group of humanitarian non-governmental organisations (NGOs), was triggered at the end of a disappointing rainy season, in anticipation of a drought, and the money is currently being deployed to tackle food security across the country using tools such as cash grants and food supplements for mothers and children.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataAcross 2022, the insurer, the African Risk Capacity (ARC) Group, an agency of the African Union, paid out $59.6m and covered 18 million people across Mali, Malawi and Madagascar as part of the agency’s “drought risk pool”. Indeed, since its inception in 2014, the ARC has paid out $124.3m in claims from eight risk pools covering more than 100 million people and transferring $1bn of risk. “The whole market is now covering around $200m of climate risk a year,” says David Maslo, the ARC’s head of business development.

African Union member states can purchase the ARC’s “parametric” insurance, a policy that makes pre-specified payouts when pre-agreed scientific triggers are met. NGOs such as the Start Network can then purchase a replica insurance policy under the same terms and conditions as the governments to increase coverage of at-risk populations.

Governments use national funds or donor contributions to purchase policies, and Start Network uses international donor funds to pay premiums. The greater the insurance coverage, the greater the payout for the humanitarian response. The size of the pay-out is based on the severity of the event, with the highest possible amount typically around six-times the premium.

“We buy insurance for those large-scale disasters that happen the least frequently but are too costly to cover on a one-off basis, such as a drought or cyclone,” explains Christina Bennett, the Start Network’s CEO.

Anticipatory insurance: “Game-changing”

Backers say anticipatory insurance is a more effective way to manage large-scale climate risks than traditional disaster relief finance, unlocking funding for early response to predictable disasters and saving lives and livelihoods in the process – at a lower cost to governments. As with any other insurance policy, it allows you to pay an amount upfront for greater protection if the event occurs, thereby allowing funds to go further. By adapting practices from the insurance and finance industries and applying them to the humanitarian sector, NGOs like the Start Network can structure, layer and stretch funds more efficiently, allowing them to protect more people.

“Insurance has been game-changing for us,” says Bennett. “It is a way of managing something that would be very costly for aid organisations and governments to cover on a responsive basis.”

It also shifts climate risks from local communities to financial institutions, which are better able to manage it. “This is what financial institutions are set up to do,” says Bennett. “It takes the risk away from people who are just trying to make a living. It is also more ethical because it prevents suffering rather than waiting for suffering to happen before you do something about it.”

[Keep up with Energy Monitor: Subscribe to our weekly newsletter]

A cost-benefit analysis carried out in 2020 by the International Food Policy Research Institute, an international development consultancy, estimated that every dollar spent on one of the ARC’s premiums delivers the equivalent of $1.90 spent on traditional humanitarian response six-to-nine months later. The study assumed pre-agreed contingency plans would reduce the costs of delivering humanitarian assistance to the poor, while improving the speed and targeting associated with the delivery of those benefits. When the long-term benefits are factored in, the additional benefits to poor households could rise to above $4.

“And even if you assume that $1 premium is going to give you $5 of coverage in the event of a very severe disaster, you will have about a 10–20 times multiplying effect between the dollar you have invested before the season as a premium to the value of what you will have received from humanitarian aid six-to-nine months later,” adds Maslo. “So, by derisking, you can create these virtuous feedback loops that reduce your overall risk.”

Although more recently deployed in Zimbabwe and Somalia, perhaps the most significant example of anticipatory insurance in action is from Senegal in 2020. Insufficient rainfall in late-2019 triggered a claim to prepare for an anticipated drought the following season. The government received a payout of $12.5m and the Start Network, working alongside the World Food Programme, received $10.6m under an ARC Replica policy – the largest-ever funding allocation to civil society for early humanitarian action.

ARC used its Africa RiskView Water Requirement Satisfaction Index to estimate the extent of the population vulnerable to the drought and the expected cost of the response. The model predicted 970,000 people could be at risk, and the payout was calculated by multiplying the number of potentially affected households by $50 – the ARC’s estimated response cost per person.

Then, throughout 2020, six Start Network members – Action Against Hunger, Catholic Relief Services, Oxfam, Plan International, Save the Children and World Vision – distributed enriched flour and made cash transfers to more than 335,000 people across seven regions. This enabled families to protect livestock and other valuable assets and avoid resorting to negative coping strategies such as skipping meals or sending children to work instead of school. The Senegalese government used its payout to support regions not covered by Start Network programming.

At the end of the response, 158,000 people had been reached with nutrition awareness campaigns and 72,000 women and children had received fortified flour. Additionally, 85% of surveyed households had improved diets following the programme and 19% fewer households went a day without eating between June and August 2020.

Political disincentives for anticipatory insurance

Despite its auspicious credentials, anticipatory insurance has some limitations as a climate-resilience solution. First, because of the increasing pace of climate change, the past is an increasingly insufficient indicator of future natural disasters, which are becoming harder to both model and insure as a result. “There is a point where the risks become uninsurable,” says Maslo. “For instance, we cannot insure wildfires in California anymore, and it is becoming more and more difficult to insure against hurricane risk in Florida.”

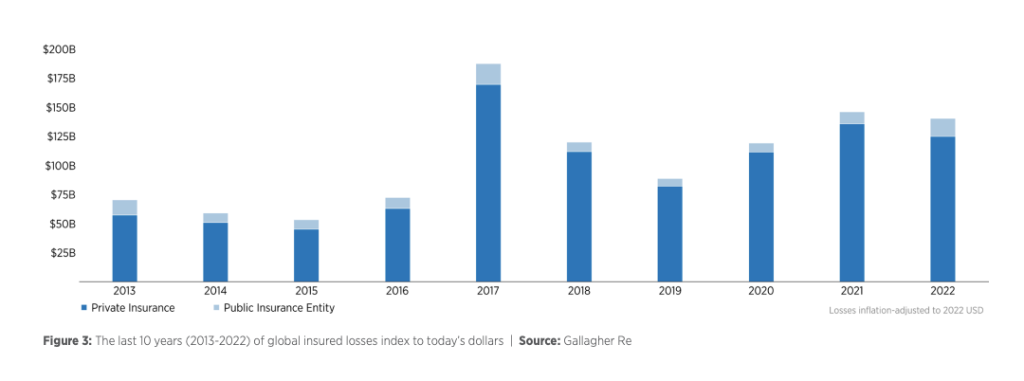

Of the $360bn of weather-related losses Gallagher Re calculated in 2022, total insured losses were estimated at $140bn, with private insurers covering $125bn and public insurance entities covering $15bn. The year of 2022 was the fifth since 2017 to cross the $100bn threshold for weather-related losses for insurers.

Because of this growing climate uncertainty, anticipatory insurance becomes increasingly pigeonholed to easier-to-predict hazards. For example, drought, cyclones and floods can be predicted months in advance, allowing funding to be put in place before they happen. “It is not a silver bullet,” says Maslo. “At most, we are covering 5–10% of the risk that the country is facing.”

Perhaps most importantly, there is a strong political disincentive for anticipatory action. The aid system, according to Bennett, is built on an undercurrent of “saviourtism”, where developed nations gain soft power from their ability to come to the rescue of their developing counterparts in their time of need. “Governments get really good headlines out of their humanitarian responses and really it plays to public opinion,” says Bennett.

Related to that disincentive is the way governments spend aid money. “If governments are going to allocate it, they want to see it spent,” says Bennett. “The effectiveness of an aid department is based on the notion that the money that comes in is spent on worthy projects with impact that can be demonstrated through fantastic statistics.”

However, using anticipatory insurance means that governments are paying premiums on a policy that may never be triggered, with the impact statistically harder to quantify as a result. “It is systemic: the money needs to go in and out of the aid department, usually within a year, otherwise they ask for it back,” says Bennett. ”So buying insurance is really hard for governments because they are buying something that they may never see the benefits of.”

New momentum for anticipatory insurance

Looking ahead, anticipatory insurance could play an important “complementary role” in the world’s climate adaptation agenda, according to Maslo. Adaptation was a key focus for negotiators at COP27 last year, and will be again at COP28 in Dubai later this year. For instance, the V20 group of 58 vulnerable countries and the G7 group of rich nations launched an effort called Global Shield at COP27, aimed at strengthening insurance and disaster protection finance.

Plus, despite its limitations, there is headroom for development of anticipatory insurance. New technologies such as AI and machine learning will enable greater data accumulation to better forecast extreme weather events and more effectively calibrate the risks to vulnerable populations. That will also allow anticipatory insurance to be used for a wider array of hazards; the ARC recently developed a product for climate-related epidemics, and is working on one for the underperformance of renewable energy assets. “Just in the agricultural space, we have the ambition to grow the market to a billion dollars by 2027,” says Maslo. “So that is five-times over the next four years.”

This type of insurance will become increasingly important for the simple reason that the risks it covers are set to become so prevalent. Research suggests that by 2030, vulnerable countries could face $580bn in climate-linked losses every year; and by 2050, urban populations exposed to extreme heat are projected to increase by 800% to 1.6 billion.

“The climate crisis has really given new momentum to [anticipatory insurance]; and, as a result, governments are now pledging real money to this agenda,” says Bennett. The growing levels of climate finance around the world could be further good news.

“Climate finance would be a lot better than government funding because there is a lot of philanthropic and private money that doesn’t suffer from governments’ issues with prepositioning funding,” Bennett adds. “So, there are a lot of reasons why the anticipatory insurance space could grow significantly, and climate finance could play an important role in that.”