North Sea oil and gas production is expected to plummet in the coming years, as renewables become increasingly competitive. Now, a new report by the think tank Carbon Tracker argues that private equity companies invested in North Sea (UK and Norway) oil and gas assets are particularly vulnerable to losses as demand falls. Private equity’s presence in the North Sea has grown steadily since the 2014 oil price crash.

In 2010, just 8% of North Sea assets were held by private companies, with the remainder owned by publicly listed oil majors and state-owned utilities. Currently, 29.7% of North Sea equity licences are held by current or former private equity-backed ventures, according to recent analysis from the Common Wealth think tank.

Carbon Tracker argues that while all upstream investors risk being saddled with stranded assets as demand for hydrocarbons falls, private equity companies are particularly vulnerable. For starters, the private equity industry is already facing “serious headwinds” as the low interest rate environment that “buoyed private markets” for the last decade “has, at least temporarily, come to an end”.

Private equity companies across all sectors are “being squeezed from both sides” as higher interest rates dampen “Limited Partner” (investors in private equity funds) demands for their services, while they find it “increasingly difficult to find successful exit routes for their investments” due to “serious commodity price risks”. Private equity companies invested in North Sea oil and gas assets are especially vulnerable due to transition risk, as well as unstable oil and gas prices, the think tank argues.

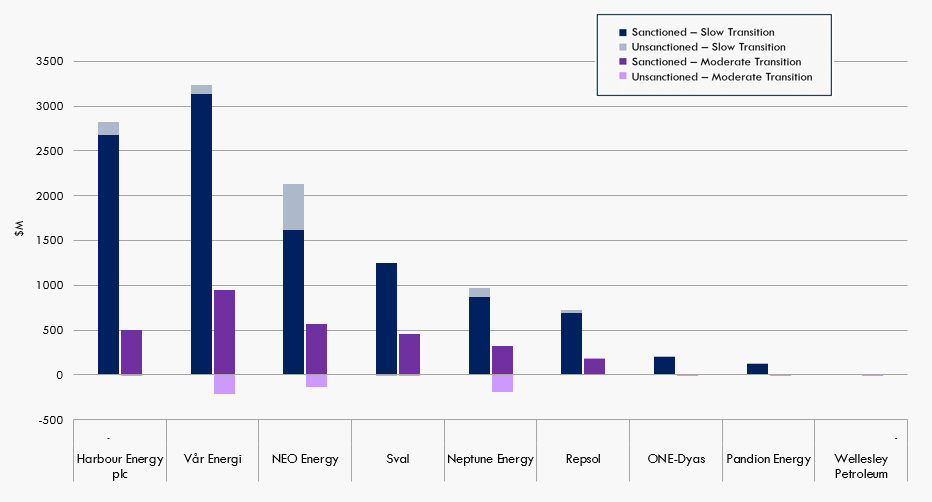

Carbon Tracker identifies ten private equity-backed companies currently active in the North Sea, of which eight are actively producing oil and gas. Each of these companies is expected to see cash flows decline by between 63% and 100% between 2024 and 2030 in a ‘moderate’ transition scenario (the International Energy Agency’s Announced Pledges Scenario (APS), which takes into account “announced” climate pledges and sees warming limited to 1.7°C).

See Also:

Carbon Tracker looks at both sanctioned (post final investment decision) and unsanctioned (new) projects. The think tank’s modelling finds that every company, apart from Repsol, would experience negative cash flows by 2030 from unsanctioned projects under a “moderate” transition.

How well do you really know your competitors?

Access the most comprehensive Company Profiles on the market, powered by GlobalData. Save hours of research. Gain competitive edge.

Thank you!

Your download email will arrive shortly

Not ready to buy yet? Download a free sample

We are confident about the unique quality of our Company Profiles. However, we want you to make the most beneficial decision for your business, so we offer a free sample that you can download by submitting the below form

By GlobalData

While Carbon Tracker’s analysis is concentrated on the North Sea, the think tank argues that it can be read as a “case study” of net-zero transition risks faced by all private equity-backed upstream oil and gas producers investing in new and existing fields.

Private equity in the North Sea: navigating peak demand

“[Companies are] chasing marginal, more expensive barrels of oil in an already difficult cost environment, [while the] likelihood of these higher-cost barrels remaining economic in a faster [net-zero] transition seems to be decreasing,” the report’s authors conclude.

Oil and gas producers have a handful of options. As noted in a separate Carbon Tracker report published late last year, these can broadly be categorised as: pursuing a strategy of natural depletion, by calling a halt to new developments; adopting a “managed investment” strategy that focuses on short-cycle projects (a strategy “at least partially adopted” by European oil majors including Eni and Shell); and finally, pursuing “business-as-usual replacement” or even production growth.

This last option appears to be the strategy favoured by Gulf major Saudi Aramco, which is expecting “global demand for crude oil… to continue to increase for many years to come”, says Carbon Tracker.

“Our recommendation for private equity firms… is that [they] ensure they model the future value of the companies [they are] invested in”, report author Maeve O’Connor told Energy Monitor in an interview.

“Incorporating future low-carbon transitions into financial planning is something that we are trying to get into even the oil industry’s head,” she added.

Given that the private equity industry is subject to far fewer macroprudential regulations like mandated stress tests or minimum capital requirements compared with the traditional banking sector, the onus lies on individual companies to assess their own net-zero transition risk, she suggests.

Nevertheless, Carbon Tracker recommends that requiring private equity investors to disclose their oil and gas investments, evaluations and associated transition risks “is one step regulators could take to protect investors”.