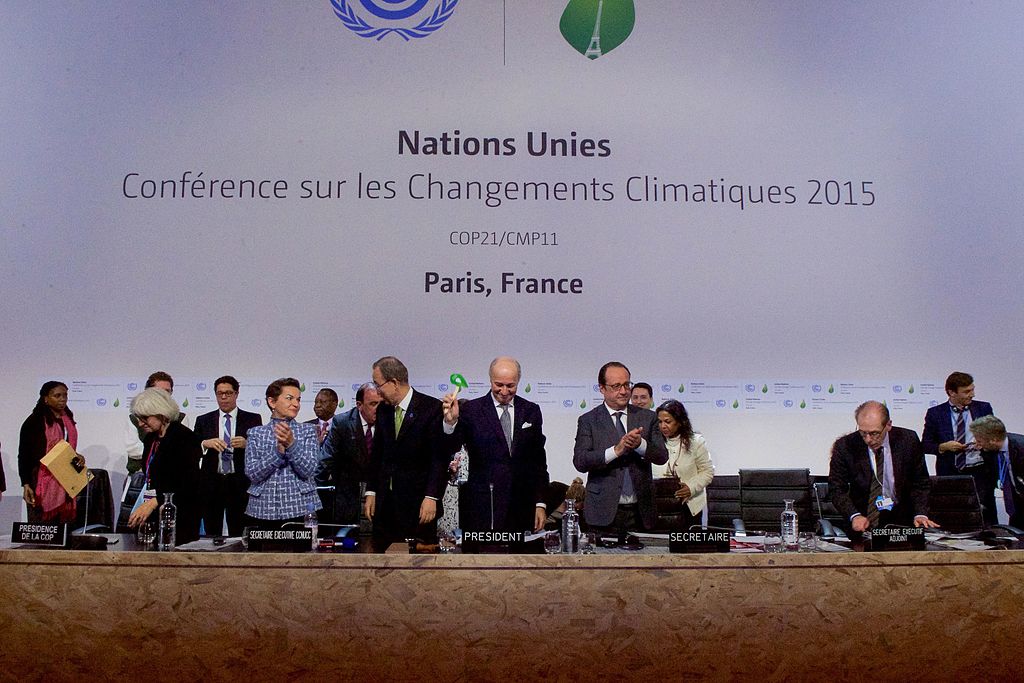

Following five years of complex negotiations, 197 nations came together to sign the Paris Climate Agreement in December 2015 at the UN’s 21st climate change conference (COP21) in the French capital. Participants agreed on a framework that aims to keep global temperature rise at least below 2°C above pre-industrial levels, ideally limiting it to 1.5°C. This requires net-zero greenhouse gas emissions – in practice, a balance between man-made emissions and removals – before 2100.

The Paris Agreement replaced the Kyoto Protocol, which was adopted in 1997 and came into force in 2005. The main criticism levelled at Kyoto was that it only bound developed countries to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions. Developing nations, including high polluters China and India, were required to report their emissions, but not reduce them.

The Paris Agreement changes that. It expects all countries to set emissions reduction goals, but invites them to formulate these bottom-up rather than imposing targets top-down.

“The Paris Agreement encompasses and speaks equally about all countries,” says Joeri Rogelj at the Grantham Institute for Climate Change in London, UK. “It doesn’t set legally-binding obligations like the Kyoto Protocol, but sets out an architecture for continuous climate action.”

National commitments

Before COP21, countries were asked to submit Intended Nationally Determined Contributions (INDCs), setting out their future plans for emissions reductions. Once countries formally joined the agreement, these INDCs became Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). These have to be updated every five years. Countries are expected to monitor, report and reassess their individual and collective goals, but those falling short of their proposed targets will not be penalised.

“This new freedom allowed governments to sign up to the Paris Agreement,” says Patrick Bayer from the Centre for Energy Policy at the University of Strathclyde in the UK.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataThe Paris agreement entered into force in November 2016, nearly a year after it was signed. By August 2020, 189 out of 197 signatories had ratified it and submitted NDCs.

The US, however, formally initiated its withdrawal from the agreement in November 2019. President Donald Trump said the Paris deal would “undermine the US economy” and put the country at a “permanent disadvantage”. As the world’s second-largest emitter after China, a US withdrawal would be a blow to global climate efforts, but it is not yet inevitable. The withdrawal would officially take effect on 4 November 2020, the day after the US Presidential Election, and democratic candidate Joe Biden has said the country will re-enter the agreement if he is elected.

Net-zero strategies

Countries were also due to submit “long-term” decarbonisation strategies for 2050 to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) before the end of 2020. This deadline has effectively been pushed back by a year, however, with the postponement of the next UN climate conference (COP26) in Glasgow, UK, to November 2021 because of the Covid-19 pandemic.

By August 2020, 16 countries and the EU had nonetheless formally submitted their long-term strategies, with the UK, France, Sweden, Denmark and New Zealand all setting legally-binding targets to reach net-zero emissions by 2050. The US had also submitted a strategy.

Climate adaptation

As well as reducing emissions, the Paris Agreement likewise aims to increase the ability of countries to adapt to climate change. It sets a global goal to increase climate resilience and reduce vulnerability. The agreement requires all countries to plan for adaptation, for example, through national adaptation plans, vulnerability assessments and economic diversification. Governments should communicate their intended actions, and needs.

The impact unchecked climate change could have on the world was starkly revealed in the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) Special Report on 1.5°C of Global Warming in 2018. The IPCC warned that without rapid and significant change, the world is heading for a 3°C temperature rise by 2100, with potentially disastrous consequences.

Whether global warming is capped at 1.5 or 2°C is “for some areas like coral reefs, the difference between dying bashfully or having a small chance of survival,” says Rogelj, who was a coordinating lead author for the report. “[The report] also shows that 2°C of warming for certain vulnerable countries and populations might be too much to still be able to pursue sustainable or economic development.”

Adaptation will be part of a five-yearly “global stock take” – the first is due in 2023 – to assess the overall implementation of the Paris Agreement.

Climate finance

The third objective of the Paris Agreement is to make global finance flows consistent with the transition to net-zero emissions.

In a report in April 2020, the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) calculated that a “climate-safe path” requires cumulative energy investments of $110trn by 2050. Achieving full carbon neutrality would require a further $20trn. At the same time, transforming the energy system could boost global GDP gains by $98trn above business-as-usual between 2020 and 2050, IRENA added.

The UNFCCC’s Green Climate Fund (GCF) was created in 2010 to help developing countries reduce their emissions and adapt to the impacts of climate change. The fund set a goal of raising $100bn a year by 2020. By July 2020, however, only $10.3bn was available.

The GCF is “contentious” and as a result “heavily underpowered”, says Bayer. Governments are “uneager” to put money into multinational funds to spend on climate projects. While the GCF is supposed to fund transformative and adaptative action, its critics argue that this has not always been the case.

An independent evaluation of the fund in December 2019 called for “significant changes”. Auditors suggested more tailored support to the needs and capacities of individual developing countries, and a greater role for national bodies in GCF projects. They also called for a renewed focus on adaptation and greater recognition of the role of the private sector in mitigation.

“The private sector is absolutely critical to achieving the Paris Agreement targets,” says Rogelj. “However, it needs to be shown a clear policy direction from governments, which can put in place incentives and long-term policy signals that drive private investments in innovation and transformation.”

Participation from the private sector in low-carbon markets opens up the opportunity to address short-term development needs, and could also ensure long-term stability for those markets. The Climate Policy Initiative, an international climate think tank, estimates that private finance averaged $326bn a year in 2017 and 2018, accounting for 56% of the total climate finance in that period.

Unresolved issues

The final outstanding issue to complete the Paris Agreement’s basic rulebook is finding consensus on a framework for cooperation between countries, notably through carbon markets. This is about fleshing out Article Six of the Agreement. It proposes three separate mechanisms, two of which are centred on markets and the third of which covers non-market approaches to collaboration.

The first proposal foresees bilateral cooperation through “internationally traded mitigation outcomes”, which could include emissions cuts measured in tonnes of CO2 or kilowatt hours of renewable electricity. The second proposal envisages a new “international carbon market” to trade emissions cuts created by the public or private sector anywhere in the world. The final mechanism describes a formal framework for climate cooperation between countries – with no accompanying trade in emissions cuts – such as through development aid.

“The issue comes down to money – who pays – and how to set up the rules in a way where you don’t have any double counting of carbon emissions,” says Bayer. “It has been held up by particular interests of certain countries.”

Brazil is the biggest nation accused of holding up agreement on Article Six. The South American country argues that its forests should be counted as carbon sinks towards its national emissions targets, which would mean it can relax efforts to cut emissions in other areas. However, Brazil also believes it should be allowed to sell credits for keeping its forests intact, which critics see as double counting.

“This is dissatisfying as carbon markets are a very good instrument, not only to raise money but also to reduce emissions in a cost-effective way,” says Bayer.

Research by the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) shows that across the regions where it operates – 38 economies in Europe, central Asia and the southern and eastern Mediterranean – collaboration under Article Six could unlock economic benefits of $53bn by 2050 and $131bn by 2100. If realised, this scenario could create a virtual carbon market valued at $300bn by the end of the 21st century.

At the same time, climate campaigners worry that weak rules around carbon markets would allow countries to meet their targets on paper, even as CO2 levels in the atmosphere continue to rise.

Next deliverables

After failing to agree on how to implement Article Six – and in particular, how to avoid double counting emissions reductions – the UN climate conference in Madrid, Spain, in 2019 (COP25) was deemed a disappointment.

Article Six is expected to be high on the agenda at COP26 in 2021. This conference will offer major economies an opportunity to build a green recovery beyond the Covid-19 crisis and provide a fresh perspective on national and global climate action following the disclosure of updated NDCs.

“This is the first time updated targets need to be put forward,” says Rogelj. “It is a huge milestone for the Paris Agreement because it will determine whether the idea and philosophy of updated and strengthened NDCs every five years actually works.”