The deep waters off the coast of California offer a tantalising renewable energy prize – an estimated technical potential of 201GW of offshore wind capacity, four times the all-time record peak power demand on the state’s grid. However, there are barriers to overcome on the path to that prize.

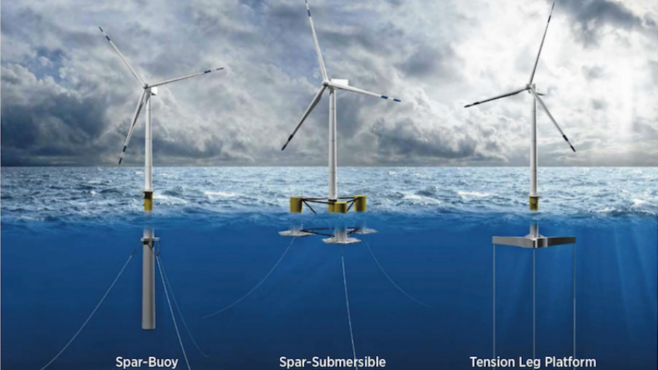

California’s deep water will require the use of floating wind turbines, an emerging technology so far limited to a few pilot projects installed globally. The waters off Humboldt County, in northern California, have the state’s best offshore wind resource, but the region lacks adequate transmission connections to the main California grid and to population centres downstate. In addition, after several rounds of negotiations between the State of California, the US Navy and the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM), the federal offshore energy regulator, have yet to resolve use conflicts over promising offshore wind development zones on California’s Central Coast.

Discover B2B Marketing That Performs

Combine business intelligence and editorial excellence to reach engaged professionals across 36 leading media platforms.

Energy Monitor spoke with Karen Douglas, the lead commissioner for offshore wind at the California Energy Commission, the state’s energy policy and planning agency, about why offshore wind would be a valuable addition to California’s power mix.

What role does the Energy Commission see for offshore wind as California plans for its 2045 carbon-free electricity target?

We are looking at offshore wind as a potential component of the resource mix. SB 100 is a statute calling for renewable energy and zero-carbon resources to make up 100% of retail electricity sales in California by 2045. Offshore wind could be very valuable because it has a very high capacity factor. The wind resource over the ocean, along the Pacific Coast, especially the northern part of our coast, is very good. Wind in general, and this offshore resource in particular, is on average pretty complementary to the solar resource that has become the least-cost renewable energy, at least during the day, in California.

We have the issue that the solar resource obviously peaks around the middle of the day and is lower in the morning and afternoon hours, and we don’t have it in the evening when the sun goes down. The nice thing is that the offshore wind resource is a mirror opposite of that. The resource picks up in the evening as the sun goes down and, after the sun has gone down, it is a very strong resource overnight. It is strong in the morning, and to the extent that it is reduced, it is reduced in the middle of the day.

The analyses that we have done demonstrate that resource diversity is a good thing. The more we can complement resources like solar energy with wind or other forms of generation with different attributes, the better off we are in terms of achieving long-term goals.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataThe offshore wind farms that may eventually be built off California’s coast would have to use floating turbines because of deep water. There are just a handful of projects globally that use this technology. Will the sector be ready for commercial-scale deployment by the mid-2020s?

From what we understand, and from what we see happening internationally, it is clear that floating offshore wind, while it is a newer technology and there is much less to look at in terms of projects that have been built at scale, is a technology that is coming. Costs are going down. The [floating] platforms and turbines that have been deployed seem to be performing well. All of that improves comfort levels, and makes it seem more likely that the technology could be ready at scale.

We are looking closely at cost because offshore wind is one of the options we could use to get to our goals, but it is not the only one. We are looking at onshore wind as well, in state and out of state. We are looking at geothermal and other renewable resources. We are trying to better understand the role of hydrogen or other possible energy opportunities, and short-duration and long-duration storage. Offshore wind is still a higher-cost alternative, and we are cognisant of that.

Researchers at the Schatz Energy Research Center at Humboldt State University recently released analyses comparing different transmission options for Humboldt – either a build out of onshore transmission or a subsea connection down to the San Francisco Bay Area. How will the Energy Commission and state planners figure out the best way to deliver power from that area?

The Northern California area off Humboldt County has a tremendous amount of potential, and while we have to look hard at fishing and other uses, it has fewer use conflicts, certainly not the military use conflicts we encounter on the Central Coast. The real challenge is that we don’t have the transmission infrastructure to export significant amounts of electricity from Humboldt County.

The Schatz Center has done a number of different analyses, with funding from the state and the federal government, to help us better understand the potential up there. One of those analyses included an initial look at transmission options and costs. The short answer, which we expected, is that there are options for exporting power from that region, but they require significant time and resource commitments. The analysis could help us justify transmission investments, looking harder at what scale is feasible or how to match the transmission side with the generation side.

BOEM had originally planned a California offshore wind lease sale for the end of 2020. When is this now expected?

If we had been able to reach a faster resolution on how to allow leasing to occur on the Central Coast it may have been possible to meet that end-of-year timeframe. BOEM’s preference has been to find a way to do a lease sale that involves both the Central and the North Coast. In part, because the potential lease area on the North Coast is quite small; it is really geared to a local project.

[Keep up with Energy Monitor: Subscribe to our weekly newsletter]

We have been working over the last couple of years with the military and had a good series of meetings with them. The military suggested some potential areas we had not included in our public outreach the first time around. We have just completed a public process to get input and comments on some of those additional areas. We have got a bit of work to do now with the Department of Defense, BOEM and our state agency partners to think about how we might find a solution for the Central Coast.

The trade group Offshore Wind California has urged the state to build 10GW of offshore wind by 2040. Does California need to set a long-term offshore wind deployment target?

There are a couple ways of thinking about that. From a planning perspective, taking a number, whether it is 10GW or some other set of numbers, and asking the question: how would 10GW support our electricity system? Is that the right amount? Is that too much? Is that not enough? Where would we put 10GW of offshore wind? What transmission investments would we need to do that? What other uses of the water, or the area, might be affected? And what would be the potential benefits?

That kind of analysis is very helpful so at a policy level we can say, ‘Well, based on this analysis, is that the right number? Maybe it should be less, maybe it should be more. Over what timeframe? Is it possible? Should it be accelerated?’”

I personally think it is early to set an actual numeric goal for offshore wind. We need to get a better handle on how we can resolve issues on the Central Coast, especially the discussions with the Department of Defense, as well as transmission constraints and opportunities on the North Coast. How does that look in terms of other possible scenarios and portfolios? The good news is that these are the sorts of analyses that are being done.